Over a year ago, President Bush and his foreign policy team took office determined to carve out a path different from their predecessors. Emphasizing core national interests over humanitarian concerns and nation building, they would stay focused on managing relations with key countries such as Russia, China, and Mexico.

But with the launching of the war on terrorism, the Bush administration has abandoned its rhetoric of arch-realism for one of robust moralism. President Bush explains the anti-terrorism offensive as good versus evil. There can be no neutrality or gray area. Confronting terrorism and its supporting "axis of evil" is now the central organizing principle of American foreign policy. What does it mean that Bush the realist has become Bush the moralist?

The president deserves credit for exposing the fallacy of moral equivalence regarding terrorism. Terrorism has been condemned for what it is: the killing of innocent people. It has duly been met with the full force of moral condemnation, law, and state-power.

It remains to be seen, however, whether Bush and his team can enter the next phase of the war on terrorism without falling victim to the hazard of excessive moralizing. Deleting the word "crusade" from his working vocabulary and jettisoning the operation name "Infinite Justice" are signs that Bush and his administration are aware of this danger. But their notion of doing battle against an axis of evil powers begs the question of how to define the logical end of the war as well as the appropriate means of achieving victory.

The best way forward may be to view this conflict through the lens of conventional politics. Ideals clash, interests clash; confrontation is inevitable. Morality guides us, but there is little that is pure or certain, and no one has a monopoly on virtue.

With this in mind, we might think in terms of moral clarity. The difference between moral clarity and moral certainty is more than semantic. Moral clarity means that we have a clear and unambiguous conception of what is right and wrong. We defend that position with moral commitment and prudent judgment. History shows us that moral certainty leads to violence; there is no other place to go.

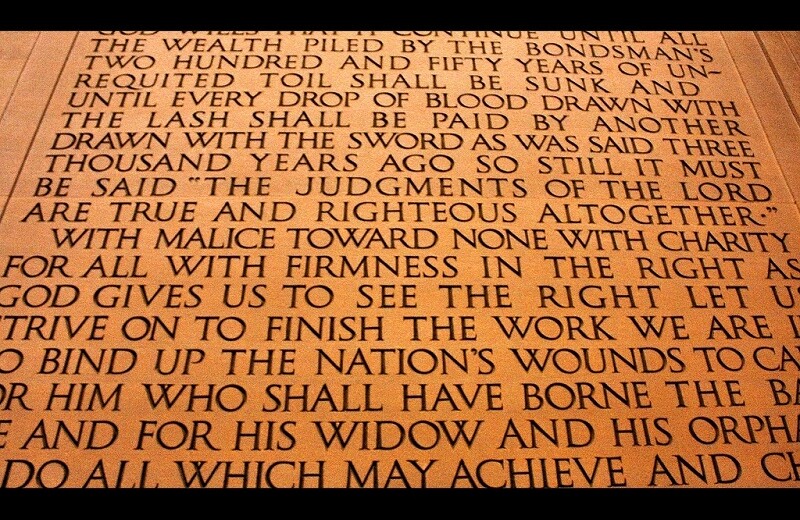

Abraham Lincoln, no moral relativist, understood human inadequacy and the perils of elevating politics to a transcendent level—a place beyond human reach. As Lincoln put it in his second inaugural, "Both [Union and Confederate] read the same bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other." Lincoln showed that even in the face of conflicting moral certainties, it is possible to be morally coherent and committed—"with firmness in the right, as God gives me to see the right"—while retaining a sense of humility. This enabled him to pursue an all-out war that could end with a chance at reconciliation: a war that could end with "malice toward none and charity for all."

In the next phase of the war, the challenge will be to avoid the shoals of crusading moral certainty on the one side and abject moral equivalence on the other. The course is there to be navigated—even if it is not yet visible nor especially well marked.