Featuring

Odd Arne Westad

Former Professor at London School of Economics and Political Science

Joanne J. Myers

Former Director, Public Affairs Program, Carnegie Council

About the Series

Carnegie Council's acclaimed Public Affairs program hosted speakers who are prominent people in the world of international affairs, from acclaimed authors, to Nobel laureates, to high-ranking UN officials.

Attachments

In this astute analysis, Westad explains China's international relations over the last 250 years from a Chinese perspective, providing valuable insights into its current and future course.

JOANNE MYERS: Good morning. I'm Joanne Myers, director of Public Affairs Programs, and on behalf of the Carnegie Council I would like to welcome you all here this morning.

To begin this program year, it is my pleasure to welcome Odd Arne Westad to this breakfast program. Professor Westad is a prize-winning historian and East Asian expert. Having spent many years living and working in China, he has been a witness to how the Chinese state and the Chinese people, with their resourcefulness and adaptability, have embraced change. In Restless Empire, he shares his findings with us.

In about five weeks' time, China is expected to hold a Communist Party Congress in which the country's leaders for the next decade will be unveiled. It's not that difficult to surmise that as China prepares for the changing of the guard, the next generation of politicians will be facing entirely new challenges across all sectors of society, from the economy to civil unrest.

While predicting the future has become a favorite pastime of those interested in China, Professor Westad believes that before we can begin to understand its probable future, we must first reevaluate its recent past, which he does very engagingly by providing an in-depth analysis of China's international aspirations of the past 250 years.

So when China-watchers are speculating about the future and asking such questions as whether China could collapse under the weight of its own domestic challenges, or whether its proactive global engagement and rapid modernization of its military will lead towards responsible and productive global citizens, or whether it will continue to use its influence to confront and undermine the interests of the United States and other powers, challenging international norms, as it has recently done in the Security Council, what can we expect? While we may not have the definitive answers, with a reading of Restless Empire we will have many clues.

Please join me in welcoming Professor Westad, who will be explaining how the past has set the course for the future.

RemarksODD ARNE WESTAD: Thank you much very, Joanne, and my thanks to the Council for inviting me to address you this morning. It is a great pleasure and it's good to be here.

Now, the book that I have written really is an attempt to try to deal with China's international affairs over a fairly long period of time from a Chinese perspective. I'm very much aware that there is a fascinating, and certainly voluminous, literature on China and on China's position in the world out there.

What drove me to do this book is really that angle of view that attempts to look at a fairly long period of time—maybe not all that long, really, by Chinese standards when you think about all of China's history, but still a sizable chunk of time—in terms of how China's world views have changed, how Chinese people—not just decision makers and politicians and military leaders, but people in general who have engaged with foreigners—how they have come to see the outside world, how they have come to interact with the outside world. That's the basic premise and starting point for this book.

It's also possible to do that now in a way that hasn't been possible in the past, because China has become a much more open society for historians to work in compared to what the situation was when I first came to China more than 30 years ago. Now you can actually use the same tools of the trade as historians would if they wrote about Western countries or Western societies. You do it with difficulties, because China is still a political dictatorship, and getting the same kind of access as you would to source materials, say, in the United States or in Britain, would be very difficult. But at least you do have some access now, which is entirely different from what has been the case before. Therefore, it's possible to write the kind of history that I'm attempting to do in Restless Empire.

As Joanne alluded to, the book is also, to some extent, a summing-up of my own experience in engaging with China. As I said, I first came to the country more than 30 years ago as a foreign exchange student, and I have been going in and out of China quite a bit since then. As many of you will know, there is probably not a country anywhere in the world that changed more during that generation than China has.

When I first came to Beijing, it was a society that was entirely different from other countries, even within its own region. Money didn't exist. If you wanted to take a friend or a girlfriend out to a restaurant, you could bring your renminbi, your money, but you wouldn't be allowed into the restaurant unless you had the political permission of your work unit, your danwei. You had to come up with a little chit that said that you and your friend would be allowed in to eat in this restaurant.

Anyone who has visited Beijing or China over the past few years and experienced the culinary feast that China is will understand this enormous transformation that has taken place during this period. Overall—and this is also a very important part of my argument in this book—it is a transformation for the better. China is not just richer, but it's also freer and opener in terms of discussion now than it probably has ever been in its history. There's much that remains to be done on that, but in terms of getting away from what was really a cataclysm, I think, in a broader political sense, that China went through in the mid-20th century, there is a lot that has been gained.

What I'm trying to do in the book is, in a way, to understand that change and point forward, to some extent, to China's future, based on what we know about its past or how we are trying to understand its past. This is contentious. There are many different ways of looking at China's past for the time period that I'm interested in.

You have to, in a way, start by dealing with definitions. You have to have a certain sense—at least I think you need to have a certain sense—of what China is in order to do a book like this. And that's not as easy to define as one might imagine.

There have been very many different definitions of what China is during the 3,000 years or so that some form of China has existed. It has not always, of course, as you will know, been within the borders that it has now.

It has also changed a lot, though many Chinese tend to deny this, in terms of culture and ideas and perceptions. Much of what is in the Chinese past, particularly the deeper Chinese past, would simply not be recognizable to any Chinese who is living today. Those of you who think that the Chinese are more apt to go back and look at their written classics in order to understand how the world works today than we are going back to Plato or Aristotle to understand how we feel about what we are seeing before us—that just doesn't hold up. It is not right. It's not how China works.

Quite on the contrary, to quite some extent, young Chinese today are cut off from much of their past. They are cut off linguistically, because they do not know the classical Chinese and, therefore, they are not able to read, in effect, anything that was written prior to the 1910s. But they are also cut off because their experience of life, of the world, is so amazingly different from what anyone has seen in China at any point before.

All the concepts and perceptions that I'll be dealing with when I speak to you this morning are contentious, and they are changeable, which is another important premise for my work on China, and indeed for this book. But let me then try a definition. I guess you have been waiting for one, since I have been alluding to this, my definition of what China is.

China is a culture, first and foremost. It's a state. It's a geographic core. Around this, identities and boundaries and definitions of purpose have shifted and adjusted for a very long time. There is very little that is constant in China. There is very little that is predefined, that is given. The restlessness that I allude to in the title of my book has to do with that. It has to do with how contentious many of these concepts and perceptions, including the concept of what China is, are for many Chinese today.

It is very important—and we can talk about that later on—to understand that China originated as a cultural definition, first and foremost. Well into the 20th century, a lot of Chinese would stick to that definition, what it means to be Chinese.

What it means to be Chinese is, first and foremost, the written Chinese language. The concept of nationality and nationalism, in our sense, if you wish—or in the European sense, I should rather say, than in the American sense on this—the German concept of nationality is Blut und Boden [blood and soil], your ethnic region and the country you grew up. That's something very new for the Chinese. Their sense of self has been culturally centered much more than centered on these kinds of issues.

But, of course, in spite of this restlessness and in spite of this changeability that I'm dealing with in the book, there are concepts and perceptions from the past, varied over time, that in content are reasonably similar, or at least have echoes that come out of China's deeper past. Some of these are very important in order to understand China's foreign affairs today. Let me just mention some of those that I think are important that do come out of the past in some form.

The first one is a concept of justice—not distributive justice in the way that we often think about it, but rather about order and about place in the world. Built into this argument about the role of justice, fairness, that direction of thinking about the concept, is the Chinese belief, held by every Chinese that I know, that China has been treated very unjustly over the past century, that China has been victimized, that it has been excluded from international affairs, that it has not been able to take its legitimate place in the world. If you listen to Chinese diplomats today—and even more so, if you listen to those who really run Chinese foreign policy within the Communist Party—this is something that comes up again and again and again, and it's deeply held.

It's not a policy, justice is not a policy, and there are so many different concepts of it that that would be very contentious even within China. But as way of trying to understand how the Chinese think about foreign affairs today, I think it is very, very important.

The way that it is expressed often now is through concepts of sovereignty, which we may also discuss a little bit later. Again, sovereignty, as I often tell my Chinese friends, is not a policy, however dear you may hold it. But it is important for the Chinese and their understanding of where they come from.

Secondly, there is a preoccupation with rules and rituals. Here one has to be careful. I am not talking about rules and rituals coming out of the imperial era. I am more talking about a preoccupation with the correct way of behavior, that things have a certain place—it's connected to what I have just been talking about, the concepts of justice—that there may even be a correct way of understanding the world, and that China, to some extent, represents that. There is a cultural centeredness with regard to this that is very important to understand in the Chinese.

Some of the Chinese preoccupation with international law—for all of China's abilities to, as most countries have to, drop that preoccupation when it really suits their own interests—their general preoccupation with principles of international law, going back to the late 19th century, is something that I think is connected to this ongoing process of trying to understand how the world works outside China. There, the preoccupation with rules and rituals and correct ways of behavior is very, very important.

Finally, there is a sense of centrality to the thinking of many Chinese about their place within the region, not necessarily on a global scale. I think it's important to understand that, in particular for those of you who know a bit of Chinese. The Chinese name for China is Zhonghua, the central kingdom, the central empire.

That doesn't mean centrality, I think, in any meaningful way on a global scale, but it certain means centrality within the region. It's deeply cultural. It means that China is the cultural root of Eastern Asia and, therefore, has a particular place, a particular primacy, with regard to how international relations in their region are supposed to work. This is very deeply held in China.

It's actually also rather deeply held by many people who would not define themselves as being Chinese within the region, though less and less so, which is one of China's main foreign policy problems, in my view.

Let me tell you a little bit about how the book is put together so that you have that before you start reading it and you can get an overview. This is not a book just about international affairs or foreign affairs in a narrow sense, about diplomacy and warfare and international conflicts, although there is a bit of that of course in it as well. If you want to do an overview, you can't ignore those matters. But I want to think about international affairs in a much broader sense than that: How the Chinese people have related to international affairs as and when they have encountered them.

This is also about emigrants and immigrants; it's about businessmen; it's about missionaries; it's about people who have interacted within this international China that I'm interested in for a very, very long time. Some of the people you meet in the book will be known to you and others will be relatively unknown.

One figure is a guy called Rong Hong—or Yung Wing, as he was known in the United States—the first Chinese who graduated from a Western college when he graduated from Yale in 1854 and later on became a key interlocutor between his own country and the West.

I write about a Yorkshire man by the name of John Fryer, who came to China as an Anglican missionary in the 1850s but became the foremost science publisher in Chinese. It's Fryer more than anyone else, through two Chinese publishing houses that he sets up in the Shanghai region, who introduces Western science to China.

Now, think about that for a minute in terms of international affairs and the significance it has for China's understanding of how the world works and its place within it. This entire revolution that happened within a decade, more or less, when Western science is introduced into China—and in some cases, merges, becomes an amalgam with, with what some of the Chinese knew from earlier on—it is essential.

I wrote about a guy called Wang Tao, from Suzhou in central China originally, who spent quite a bit of time in a tiny little town in Scotland called Dollar, of all things, where he sat translating the Confucian classics into Chinese and, at the same time, observing the Scottish industrial revolution and communicating what that led to, to his Chinese readers—fascinating stuff. Here we have this guy translating the Chinese classics from 3,000 years ago while he is seeing how the landscape around the place where he is staying in Scotland is being changed by the telegraph, by steam engines, by railways—all of that. He is horrified, by the way, he's absolutely horrified, as a Confucian, in terms of what he is seeing: How can people think that they can actually change what the landscape looks like, what nature looks like?

Finally, a guy called Xie Yichu, originally from Guangdong, who ended up in the interwar period as the richest man in Thailand, in Bangkok, and whose holding company is now the biggest foreign investor in China in terms of foreign direct investment—seen, of course, as coming from the outside. But Xie and his family are both insiders and outsiders. They are Chinese in origin, but they also are very Thai. They have a Thai name and a Chinese name. That Chinese diaspora plays a very important part in this book.

Now, my students, as you may imagine, have been asking me as I have been working on this book, "Professor Westad, what is your interpretation of China's foreign policy over the past 250 years?"

Of course, I have to disappoint them. I do point out, "You need an interpretation for what you are doing. I'm not so sure I need one for this book."

I may be wrong. At least I found it very difficult to come up with one. I mean there is a set of significant positions in the book, though, that are important for understanding where I'm coming from.

I think this is the most important one, that the making of modern China was in many ways a metamorphosis. It created a hybrid form of society and a hybrid form of state, from domestic and from foreign influences alike. There is much more that is international with regard to China than we often realize, including, of course, the form that the state has at present, which is almost entirely a Western import, through communism and through other influences.

I also talk in the book, of course, about the kind of state and the kind of society that contemporary China inherited from the Qing empire—a great, aggressive, outward-looking empire from the 17th up to the early 20th centuries. For those who want to talk about China as sort of backward-looking, for those who want to talk about eternal China, unchanging China, look at the Qing. There's nothing inward-looking with the Qing at all. At least no one who got in the way of the Qing empire would see them as being inward-looking. This is a powerful state—probably in the early 18th century, when my story starts, the most powerful state in the world, at least within the territory that they operate in. Of course, they left a very significant legacy to China today.

First and foremost, the way China looks, China's borders. That's the other part of the title, empire. China is the only empire that exists today, trying to behave like a nation-state, which it most definitely is not, which has kept its borders more or less intact from the late imperial era.

There are some changes. A part of Mongolia, for instance, that used to be within the Qing empire is now outside.

But in spite of all this talk about decline and collapse for more than 100 years, even in that period, the successors to the Qing, including the present People's Republic, were able to keep the borders remarkably intact—which, of course, leads to some challenges and difficulties today that I'm trying to deal with.

The economic and social transformation of the late 19th and early 20th century is important in the book. It's not just important for historical reasons. It's also important because I find a lot in that time period that is a little bit similar to China today. It certainly is a lot closer to China today than what the death of the early Communist experience has been—the first attempt in a long while to take China entirely out of the international society and turn it inwards. It failed spectacularly and tragically, tragically for the people who died as a result of it. But it is an exception. The late 19th and early 20th century is much more similar to the period that we see today.

I'm talking about this in terms of China's modern transformation. The point I want to leave you with on that is that this is a transformation over into a form of modernity that happens roughly at the same time, in its most advanced form, as it happens elsewhere.

Urbanization, people coming into the cities, the beginning of an industrial economy in pockets within China, happens roughly at the same time as it happens here or it happens in most of Europe. It's small compared to the overall size of the Chinese population, but it has been ongoing for a very long period of time. I think it's important to understand that. On many of the issues that we are preoccupied with today, China is not a newcomer in terms of international affairs and in terms of the background to it.

Let me just very briefly, and in conclusion, sum up some of the key challenges that I see with regard to China's foreign affairs today, coming out of the past.

One I have already mentioned, borders and neighbors. China's borders are imperial. Within them live a very large number of people who have not traditionally thought of themselves as Chinese, though you may read in Chinese textbooks today, of course, that they have been Chinese forever—without knowing it themselves, of course.

China's focus is on its role as a regional power. It will remain its focus for a very long period of time. China is not aiming at, and doesn't have the capability to play, a broad global role, which is something that they may regret, given the financial and economic importance that China has.

But for the time being, China's interest in immediate foreign policy terms is turned towards its own region, which is a very problematic region, of course. There are lots of challenges we have to deal with.

For instance, if you have one formal ally in the whole world and that ally is North Korea, you don't have an asset; you have a problem. You have a very, very big problem. The Chinese are aware of this, but haven't really been able to find ways of dealing with it, at least not dealing with it efficiently. I think that shows part of the immaturity of current Chinese foreign affairs, even when dealing with its own region.

The focus on technology and trade is something that I think it's very likely will go on in China for a very long time. The importance there, I think, to those of us who look at China from the outside is, first and foremost, of a comparative kind.

It goes back to what I said about the breakthrough of a form of modernity—call it a capitalist modernity—in the late 19th and 20th century in China, roughly at the same time that it happens elsewhere.

China, as it has risen to a global position, global eminence, is different from any rising power on that scale that we have ever seen before. The main difference is not, in my view, as some people claim, based on a different culture or a different history. It is in a way the opposite. China, as it has risen to its current position, is more integrated into the world economy, on a broad scale, than any other rising power has been in history, including this country when it rose to prominence in the 19th century.

Many of you will know this already, but I think it is important to underline the degree of integration with what is happening globally and certainly, first and foremost, within the region itself that China has at the moment.

The amount of foreign direct investment into China is a good yardstick, a good measure for that. When the rest of the East Asian region industrialized, more or less spending the whole 20th century, starting with Japan and going through Taiwan, South Korea, parts of Southeast Asia, of course there was some foreign money in that, but generally not all that much.

China is entirely different. In the export-oriented high-tech—the most productive part of the Chinese economy at the moment—about 60 percent of the invested capital comes from foreign direct investments, comes from FDIs. That's unique. No other power has risen to international prominence under these kinds of circumstances before.

What will it mean for China's future? We don't know. But it certainly means that, in spite of what the government often tries to say, China is much more dependent on what happens internationally than any other power that you can compare it to that has been at its stage.

Finally, what I think is China's biggest problem today is that it is very poorly governed. China's government, the party-led regime that we have at the moment, doesn't fulfill many of the aspirations, many of the needs of its people. Of course, this could be said about many governments around the world with some degree of truth.

But there is a particular problem in the Chinese case because China is a political dictatorship. You do not have the opportunity for the kind of open—at least not entirely open—political debate, or indeed to chuck that regime out at the central level or in the provinces when you have had enough of it. This is a significant problem in China today, not because most Chinese go around on a daily basis feeling extremely oppressed or wanting deep political change, but because, particularly among younger people, there is an increasing sense that this regime is not able to handle the country's problems. I think it's important to realize that when you look at China from abroad.

This is not a kind of revolutionary situation, though it may turn into one if its economy becomes much, much worse than what it is today. But it is a gradual increase in disaffection with how the current regime is handling matters inside China and outside China.

So I think, whatever happens on this particular issue in terms of the development of China in the future, the search for better governance, domestically and in terms of international affairs, will be a very significant part of it. Those who think that China will remain the way it is today for a very long period of time are certainly almost entirely wrong. This is, in a way, what Restless Empire is about, about the restlessness and the changeability and the hybridity of China.

Thank you very much. I'm looking forward to your questions.

QuestionsQUESTION: Susan Gitelson.

Thank you for sharing with us your well-informed thoughts about what's happening in China. But there's so much more that we want to know.

Let's start with your last point about leadership and how this is being changed. Who makes the decisions about international policy? What is the effect of the economic changes? The Central Party, after all, has access to many assets that other people do not; therefore, they have interests based on that. But at the same time, as there is an expansion of industry and other economic areas, there are more people who develop interests, such as trade, that have to be accounted for in foreign policy.

ODD ARNE WESTAD: That's entirely right.

One of the biggest challenges in terms of understanding Chinese foreign policy today is understanding how it's made. It's made in ways that are very, very different from what we are used to.

The Foreign Ministry, as such, has a relatively modest role in terms of how Chinese international affairs are constructed. It's directed by a relatively small group of people within the Communist Party, some of whom are working in the international department of the Central Committee. But there are other institutions as well.

The key institution, by the way, the one that you really want to get information out of, is something called the Small Leading Group on Foreign Affairs, which is a politburo-level grouping with a staff that is tremendously influential in terms of how international affairs are set up.

On the link to its economic development, I think one has to be careful here, because, as I said in my talk, China's economy is much more driven by the same market imperatives that we often see in the West than many people tend to think.

It's true that a significant part of the institutions that produce China's output are owned by the government. But the vast majority of these companies now operate as if they were private companies. Their main role is to deliver in terms of their bottom line. That's what they are there for. Their market behavior is, within China and outside China, rather indistinguishable from that of private Chinese companies.

On the other hand, as I pointed out, China is a political dictatorship. The government believes that it has both the power and the authority to act in a way that our governments cannot with regard to private interests in furthering the country's international affairs. But what we are finding today is that often when China tries to do that, when the Chinese Communist Party tries to do that, it doesn't work. People are coming back to them saying, "Why should we do this?"

The answer is, "You should do it for the country and you should do it for the state," which companies would do, but only if it also served their bottom line, if it served their immediate economic interest.

This is incredibly important for China's foreign affairs today, to get that picture right. I sometimes feel that we fail in doing that. We think about China far too much as one unit reactor with regard to international affairs on issues like resource exploitation, for instance, or exploring in different parts of the world. It's more complex than that.

QUESTION: Ron Berenbeim.

China's economy, at least in my understanding and I think a lot of other people's, is fundamentally export-driven, with an undervalued currency. This creates problems for the future. If its currency were properly valued, it would have growing internal markets who could afford their goods. Right now I would guess that about half of China is not the China we all know and that you described. That's coastal China.

What do you see in terms of the future in terms of a rebalancing of their economy?

ODD ARNE WESTAD: I think you are entirely right in saying that part of that rebalancing is tied up with the question of currency reform, about basically making the yuan an international instrument of exchange, which it can't be at the moment because it's not fully valued in terms of international markets.

One has to be careful again here not just to focus on convertibility and nonconvertibility. That's a minor part of this whole issue, in my view. This is really about how you spend the yuan internationally, how you can use it internationally. Of course, those two questions are connected, but they are not identical. They are not the same.

In terms of the future, I would have thought, when the last decade started, that during that decade the government would realize the importance of its own domestic markets gradually, as its economy grew, and therefore carry out the kind of currency reform that China needs.

What happened with the economic crisis in 2008—really, for China, it was a 2007-2008 economic crisis in many ways—was complete retrenchment with regard to this, which leads to, to put it mildly, a dichotomy in terms of China's international economic policy.

What you have is, on the one hand, Wen Jiabao, the current prime minister, running around the world upbraiding other countries, including this country, for not being good enough capitalists, for not doing the job properly. It's really quite something to see a representative of the Chinese Communist Party in Davos last year upbraiding everyone who was there, saying, "You are breaking the rules of the game. You are not acting the way international markets and international exchanges are supposed to happen." So you have that on the one side.

On the other side, they are refusing to bring the yuan up to a reasonable value in terms of other currencies, thereby undermining many of the rules of the game.

I think this comes back to what I said initially about rules and regulations, in terms of international society and how the Chinese see them. They see the principle that can serve them, which basically is very open market- and trade-oriented, but they can't quite bring themselves to act on this as far as it has to do with China. That may be a foreign policy, but it certainly is not a very good one.

QUESTION: Jim Traub, with Foreignpolicy.com.

I want to ask you a little bit about this restlessness you describe in relationship to an expression the Chinese used to use a lot, which is "peaceful rise." I think for a long time people took some kind of solace from this idea that China was so preoccupied with working out its internal contradictions that, in fact, "peaceful rise" was a meaningful expression.

Now, of course, there is an enormous amount of anxiety about China's aggressive movement into the South China Sea and elsewhere, which implies that perhaps the Chinese have now reached a level of confidence where they no longer need to reassure the world that their rise will be peaceful and are prepared to have a somewhat more frictional rise than appeared to be the case. How do you understand that?

ODD ARNE WESTAD: This is what the Yale historian Paul Kennedy, in a different context, has summed up very well as "imperial overstretch." It is what happens when you think that others in terms of their overall influence and position, including their material position, in a broad sense in the world, have been in decline for some time and you, therefore, can assert yourself more within your own region, which is important and part of the question that you pose.

I think on some of these issues—and the South China Sea conflict is by far the most important one—China's recent foreign policy, in the last two years, year-and-a-half, has been pretty disastrous. They have been able to undermine within a very short period of time very patient work, going on for almost 20 years—more than 20 years in some cases—to bring the crucial region—crucial to them and crucial to the world—of Southeast Asia closer to them.

Within a very short period of time, they have been able to undermine all of that by the way their demands on access to what they believe and most people now believe are quite critical amounts of resources in the South China Sea—how that has been presented and how that has been pushed.

It shows some of the weakness in Chinese foreign policy overall, whether it's an overall turn in the direction of a more aggressive behavior or a more forceful behavior—put it that way—internationally.

I don't know. I'm very doubtful about that. Much of the discussion about these kinds of issues now in China is pretty open. I have participated in some of them with officials from the party and from the foreign ministry.

Many of these guys understand that what they have done with regard to ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] and what they have done with regard to the South China Sea has not served China's interests, and they are trying their best now to get out of it, back away from it, and return to what they now have started calling all of a sudden Deng Xiaoping's approach to Southeast Asia—maybe a bit too late in the case of a few countries. But we will see.

Internationally, I think what's going on at the moment is an attempt to figure out what China's real interests, in a broader sense, actually are, to develop, if you could use that term, a "grand strategy" for China's rise, China's emergence in the world. But that grand strategy—if indeed it does exist—is very unclear. It's very uncertain what China wants to do in a broader context. It has a fairly good sense of what it wants to do within its own wider region, but as soon as you get out of it, as you see with Libya or with Syria now, Chinese diplomacy stalls. It goes back to principles.

As I said earlier on, there's a lot of talk about sovereignty. That's fine. Sovereignty is a wonderful principle. But it's not a policy. If you are supposed to be a rising international power, you are also supposed to lead, at least to some extent. And China is not doing that on many of the critical issues outside its own region.

Maybe part of the reason for that is that it's so unclear to many within the Chinese leadership themselves what China would actually want to achieve. That's a difference, if you think about this as at least a gradual power shift in global international affairs.

When this country rose to international prominence, it took a very long time, but it was a gradual getting-together of a set of concepts, of ideas about what America wanted to do in the world—contentious and much-debated, but still cohering around the middle part of the 20th century. China doesn't have that. What China wants at the moment is not to change the international system. It simply wants more for China within that system. That's crucially different from much of what we have seen before.

QUESTION: Martin Sadjik. I'm the permanent representative of Austria here at the United Nations, and I served as ambassador to China before coming to New York.

It's actually difficult to put a question to you because I agree with so much of what you have been saying. But let me underline some points that I think are really important for the understanding of what you have been saying.

First, you were dealing with the inferiority complex. That is, if I may say so, something that is at the moment really the issue in China, which is a paradox. The more China rises, the more they cultivate the inferiority complex. It is cultivated by the party, because it is the platform for nationalism. You see it now. As soon as they have internal problems, they cultivate nationalism and they cultivate their inferiority complex. On this platform, everybody agrees in China.

I think we will have that more in the future with more self-assertion of China. We will have to live with this paradox that we foreigners have so many difficulties to understand. It will be there.

The other thing that I think is important, also with the way you presented it, I think in this built-in inferiority complex is a drive to put China back at the position it was before what I would call the Boxer upheaval, when China really crumbled, when China lost its sovereignty over Korea. What they do now is to get this back. They did not only lose sovereignty over Korea, they lost Taiwan, they lost the islands, which is all in the period around, if I may say it in very general terms—and you will do it better—1900.

So what they do now is drive back China to its old glory, the glory around the turn of the 19th to the 20th century. We will see a lot of that also in the future.

One of the main points is the interrelationship between China and Japan. When the Chinese will have, from their point of view, accomplished that they are bigger and better than the Japanese, then we will see something else in the interrelationship in Asia.

One other point is on the presence of China outside. It is also a paradox. The more China is export-driven and, as you rightly said, connected with the outside world, the more it is also dependent on the outside world. But it doesn't have the structures.

We saw it in Libya. The crisis in Libya—not now; the relationship to the crisis in Libya—how did they deal with the 40,000 Chinese workers in Libya that had to be evacuated? The Chinese don't have the structures for this. I don't know whether this is really clear here in the United States. Who evacuated the Chinese from Libya? The Europeans. They had to turn to the European military forces to help them to evacuate the Chinese workers to Malta and to Greece. They are not able to do that themselves.

They don't have also the people. They don't have the people who work for companies to deal with the growing outside presence of China. When they first tried to build a motorway in Poland, they underbid the prices incredibly and then they failed. Then the foreign minister had to go and excuse himself directly to the Polish government, because it simply failed.

Finally, the last remark is what you said about governance. I think this is also very important. There is this theory—and this is maybe my only question to you—that China is actually run like a dinosaur. The dinosaurs had very, very small heads—a huge body and a small head. If you look at the Chinese government, truly very few people—it's a very small head for a huge body. Will that continue like that?

ODD ARNE WESTAD: Thank you. I'm not going to comment very much on this, because I think we agree on most things. But very quickly, on two points that you brought up.

On Japan, which I didn't deal much with in my talk—I deal with it a great deal in the book—it's very central for China's international affairs, and has been historically, in a rather catastrophic manner, as we know. Much of that history lives with us today.

Part of the reason—not the whole reason, but part of the reason—why the current relationship between China and Japan is so disastrous is, of course, based on different perceptions of history, of what went on in the past. One shouldn't exaggerate it, because that history is very often used as a political tool in the present, more than being about remembrance. But there is a sort of seamless integration of those two aspects of China's Japan policy that really worries me. It worries me in terms of what I earlier on called, deliberately, the immaturity of Chinese foreign policy.

The Chinese leadership knows that if it is going to get anywhere close to the role that it had, itself, which you alluded to, earlier on within its region—say early 19th century or thereabouts—it has to have a decent relationship with Japan. As long as Japan remains a staunch U.S. ally—as the Chinese sometimes call it, an unsinkable American aircraft carrier in the Pacific—China has no chance of becoming predominant within its own region. Still, they are trying their very best, as are often the Japanese, to destroy that relationship, to make it more difficult to have a reasonable working relationship with Japan. If you ever had a case of foreign policy immaturity, I think that would be it.

QUESTION: John Richardson, professor.

About 20 years ago, a French politician and intellectual Alain Peyrefitte wrote a book called The Immobile Empire. It was about an expedition from good old George III to China in the 1790s. The book is very long, and it's wonderfully descriptive of lots of things. But my take on the whole thing was that the whole purpose of the Chinese response was that they wanted the dignitaries to kowtow to the emperor. That was the whole book. That's really what it was about. The end of the story.

Today, obviously, I can see, from what you have been saying, that Japan may be forced to kowtow to China, from history. Who else is going to have to kowtow to China, ultimately?

ODD ARNE WESTAD: It's fascinating that you are referring to Alain Peyrefitte's book, The Immobile Empire. Of course, the title for my book is a direct response to that title. It is not immovable; it is changeable, it's restless—which I would say is also true for the late 18th century, by the way.

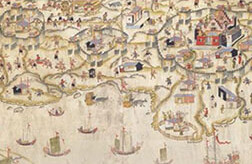

I don't think this was about kowtowing at all. I think it was about relative position within the region. The Qing knew much more about the world than they sometimes wanted to give the impression of. If you look at old buildings in Beijing, particularly if you go to the old Summer Palace, which plays an important role in my book, you will see that it was built by an emperor who employed some of the best Baroque Italian architects and designers and painters and knew a bit about the world and was able to make use of it.

For today, I think it is to some extent about relative position as well, though in an environment that has changed almost entirely. Some Chinese may think that some form of kowtowing, in the sense of respect—a term that the Chinese employ very liberally in terms of international affairs—that is important and that's something that China will move towards. If they do, they really have their work cut out for them because of what has happened in the region.

The region that China is operating in now has some of the strongest nationalisms in the world—think Korea, think Vietnam. The idea that these could in any meaningful way be submerged into a Sino-centric East Asia is, putting it bluntly, bonkers. It doesn't work. Quite on the contrary, it will produce endless conflict if China is trying to move in that direction.

I thought for a very long time—going back to the Southeast Asia question that we had—that the current two generations, the present generation and the next generation, of Chinese leaders had realized that their centrality now would have to be gained through integration, that this is about trade and economic relations, about technological development, to some extent about soft power, which China at the moment has almost nothing of, in my view.

We run a training program for Chinese diplomats, and one of them came over to London the year before last with the intention of writing a thesis about China's soft power and, after six months, concluded that he couldn't, because China had no soft power.

That's what they have to do. At the moment they are not doing it. They are not moving towards integration with themselves at the center. They are moving away from it.

QUESTION: Good morning. Thank you for your presentation. I enjoyed it immensely. My name is Rick Weaver. I'm a financial analyst and China watcher.

I was wondering if you could help the audience understand how U.S. policy is being perceived in Beijing. Specifically, on the one hand, economically we are negotiating for our biggest companies, from Apple to GM to Tommy Hilfiger, to have their increased market presence in Asia, but at the same time—the exact same time—our Department of Defense chief is going around Asia, and there's this pivot towards the Pacific with our U.S. Navy, and we're pointing guns at the region specifically.

Two questions. How is that being perceived in Beijing? Second, is that a sustainable policy over the long run?

ODD ARNE WESTAD: I think the answer to the last one is probably yes, I do think it is sustainable. It might not be very coherent, but it certainly is sustainable, because the United States, as the leading global power in strategic terms—as it will remain, in my view, long after China has become the world's largest economy—can have a policy that is, at least to some extent, in pots. Leading powers do that, and they don't necessarily suffer, at least in the short run, very much for it.

On the first question, how this is perceived on the Chinese side, I think with some degree of understanding. Chinese rhetoric with regard to the U.S. role within the whole region can at times be very harsh. I think there is still, though, a clear understanding within the present leadership that the United States has a role in Pacific Asia, simply because it is the world's leading power on a global scale. It's not as if it is a Chinese strategic aim, for anyone that I've met—whether in the party or the government or the military or the intelligence community—to aim at driving the United States out of Asia. It's more what I talked about earlier on—more for China in it.

That's an important part, I think, for combining those two aspects of American foreign relations as well. As China is becoming more important to the United States in economic terms, the right way of approaching the Chinese regime—any Chinese regime—is, of course, to try to integrate China further into a world economy and a global system that the United States has, after all, more or less created. It builds on something that Britain set up a long time ago, but it's basically an American creation. As long as China is comfortable with being integrated into that kind of system, I think we all should be very thankful, because it means that as China rises, the potential for conflict over some issues—not all issues, but some critical issues—is reduced.

I also think it's very important for the U.S. government, for the next administration, to be even more concrete in terms of dealing with China than the present administration is on trade issues, on regional conflicts. When I say concrete, I think it is important for the United States to explain very clearly to the Chinese or to anyone else within the region what American policies actually are.

On Korea, for instance, which, in my view, is the most dangerous potential conflict in the world today because of the presence of nuclear weapons in the hands of a very, very unstable regime, it is of critical importance, based on some form of concept of national interest, that the United States and China pull much closer together than they are doing at the moment. If that—or, as people would say in Beijing, when—regime collapses, because the Chinese do not think that it will survive, cooperation between the United States and China is essential. That can't start then. It has to start now, in many ways.

JOANNE MYERS: I know there are many more questions, but our time is up—which is a good thing. That means that your introduction to the vagaries of China was excellent. Thank you.