How do you balance security and civil rights when protecting New York City, America's most enduring terrorist target? NY Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly discusses the controversial "stop and frisk" law, the role of technology and police stationed overseas, and publicly announces the expansion of video recording of post-arrest statements.

JOANNE MYERS: Good morning. I'm Joanne Myers, director of Public Affairs Programs, and on behalf of the Carnegie Council I would like to thank you all for joining us as we welcome the legendary New York City Police Commissioner Ray Kelly.

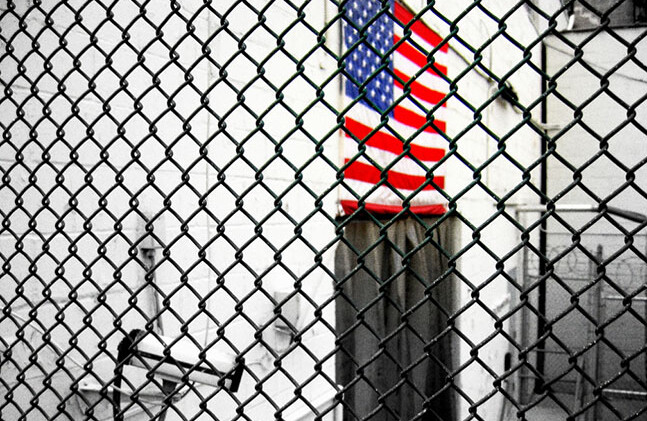

Today he will be discussing a subject that affects all of us, and it is one that I know the police department thinks about nonstop, which is to say how to ensure our safety while balancing security and civil liberties in the post-9/11 era.

There is no doubt but that the tragic events of September 11, 2001, changed our perception of the world, especially as it relates to issues of security. Phrases like "asymmetric conflict," "global war on terrorism," and "nonstate terrorist organizations" have found a place in everyday conversation as easily as long waits in airport security lines have found a place in our everyday travel.

As we are discovering, today's threats are different from the various other dangers we have faced throughout our nation's history, and the goal is to be as effective as possible in intersecting and obstructing any plans that the terrorists may have.

But often, with terrorism, it is difficult to know who constitutes the threat, where the threat might appear, and what the targets might be. This, in turn, creates pressure for information gathering and for legal enforcement tools that are quite different than those required by a legal regime focused on traditional criminal investigation and law enforcement.

As a result, the New York Police Department [NYPD] has responded to this challenge by creating a unique counterintelligence-gathering capacity that is recognized worldwide. The mere fact that at least 14 full-blown terrorist attacks have been prevented since that fateful day is testimony to the effectiveness of our police force and the skills of its commissioner.

Still, given that New York City is the number one target for terrorists, I believe we can appreciate that in keeping us safe some questions have been raised about whether the tools being used by the police to gather the information needed to prevent attacks are always the right ones.

Which brings us to the topic of our discussion today, which is how Commissioner Kelly and the NYPD are going about meeting the ultimate challenge for policing in the 21st century. How are they keeping us out of harm's way while protecting our rights as citizens? Are we making the right choices? What are the tradeoffs?

To learn more about the stellar ways in which this is being done, please join me in welcoming the personification of New York's finest, the indefatigable New York City police commissioner, Ray Kelly.

Thank you for being here.

RemarksRAY KELLY: Thank you very much. Thank you, Carnegie Council, for inviting me today. And I want to thank you for everything that you do to promote the intelligent, ethical solutions to so many of the challenges that we see in the world today.

I have been asked to talk to you about the balancing of security with civil liberties in our post-9/11 world.

Let me say that for the New York City Police Department this is not a theoretical issue; it is something that we put to the test every day in practice. The question is how the balance gets struck and what it looks like in action. I want to offer you three important examples.

The first is an initiative that speaks to the NYPD's willingness to embrace technology to strengthen the administration of justice. Today we are announcing the expansion of the video recording of post-arrest statements to every precinct detective squad and some specialized units in the New York City Police Department. We will become the biggest law enforcement agency in the country to undertake video recording.

This effort is in keeping with the aim of both the Innocence Project, a national organization dedicated to exonerating wrongfully convicted individuals, and the New York State Justice Task Force, led by Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman, on which I serve as a permanent member.

To cite the task force recommendations: "Recording can aid not only the innocent, the defense, and the prosecution, but also enhance public confidence in the criminal justice system, by increasing transparency as to what was said and done when the suspect agreed to speak to the police."

Furthermore, electronic recordings may help to lessen concerns about false confessions and provide an objective and reliable record of what occurred during an interview. As the task force also notes, this prevents disputes about how an officer conducted himself or herself or treated a suspect.

In 2010, I asked a team of department executives to look at this practice in-depth and update the research that we have done over the years. They found that the technology available had improved and that the equipment had become less expensive.

In speaking to jurisdictions that have already implemented the practice, they found there was a lot of enthusiasm but little hard data as to how it had affected cases. So we decided to launch our own pilot in four detective squads and Brooklyn and the Bronx, and we have been encouraged by the results.

We began by recording only the post-arrest statements of those charged with felony assaults. That's because we make about 400,000 arrests a year. We had to keep our pilot manageable.

Many assaults involve domestic violence. These are cases in which the arrestee typically wants to speak with the officers and makes admissions relatively quickly, as opposed to homicide cases that can involve hours of questioning.

In total, we recorded approximately 300 interviews. While many of these cases are still in process, I can say that we have secured a number of early pleas after turning over a video confession to the defendant's lawyers.

Based on this experience, we are ready to move forward with this practice in all of our commands and to expand it initially to include murders and sex crimes.

In its final recommendations, the justice task force also called for legislation mandating the recording of post-arrest statements. We don't intend to wait that long.

We believe there is a growing expectation on the part of juries that interviews be recorded. Call it part of the "CSI effect." I'm referring, of course, to the hit television show that has popularized the role of technology and forensic science in solving crimes. It has helped to fuel an assumption that these tools are a given in law enforcement. We want to continue to stay ahead of the curve, with the help of our recording initiative.

Now, funding is an issue. There's no allocation for this expense in our current budget. For that reason, we've decided to turn to the New York City Police Foundation once again for help. The president of the foundation, Susan Birnbaum, is with us this morning.

For more than 40 years, the foundation has marshaled private support for needs of the department that lie outside of our budget. In recent years, those needs have included technology for our Real Time Crime Center, which is a state-of-the-art computer facility that we opened at our headquarters in 2005, and our International Liaison program, in which we post senior officers to police agencies in 11 global cities.

For the first phase of this project, we are seeking a grant of $3 million. To install this capacity in all of our 76 precincts will be a major undertaking, no question about it, but one to which we are firmly committed.

Many of our facilities are antiquated. There's very little space to dedicate to video recording. Buildings must be refurbished to accommodate the new technology. Officers must be trained in the new procedures as well. Accordingly, we have assigned a senior officer to lead this project full-time.We are very optimistic about the use of recordings to strengthen prosecutions and enhance public trust.

Since 9/11, the legal questions that we face have only grown in complexity. We must safeguard civil liberties and guard society against acts of terrorism.

More than a decade after 9/11, New York remains the most enduring terrorist target in America, if not the world. We have been the subject of 14 different plots. It is essential that the police department's efforts to defend against terrorism be proactive, that we find those who are in the earliest stages of planning violent acts.

Contrary to what some in the media have alleged, we are authorized by law to do precisely that. Since 1985, the police department has been subject to a set of rules known as the Handschu guidelines, which were developed to protect people engaged in political protests.

After 9/11, we were concerned that elements of the guidelines could interfere with our ability to investigate terrorism. In 2002 we proposed to the federal court that monitors the agreement that it be modified, and the court agreed. We imposed on ourselves the strictest interpretation of political activity by treating every terrorism investigation as being subject to Handschu.

Let me also say that no other police department in the country is bound by these rules, which restrict police powers granted under the Constitution.

The guidelines state clearly that in its effort to prevent terrorist acts, the NYPD must at times initiate investigations in advance of unlawful conduct. In other words, a criminal predicate is not needed. Handschu entitles members of the department to attend any place or event that is open to the public, to view online activity that is accessible to the public, and to prepare reports and assessments to help us understand the nature of the threat.

As part of our counterterrorism activities, we try to determine how individuals seeking to do harm might communicate or conceal themselves. Where might they go to find resources or evade the law? Establishing this kind of geographically based knowledge saves precious time in stopping fast-moving plots.

In the same vein, we also know that while the vast majority of Muslim student associations and their members are law-abiding, we have seen many cases in which such groups were exploited. Since 9/11, some of the most violent terrorists we have encountered were radicalized or recruited at universities.

In 2006, after a series of al-Qaeda plots involving university students and members of Muslim associations in the United Kingdom, we began a six-month initiative to search open sources for signs of such activity in our area. We did not look at these groups on the basis of their religious affiliation. We looked at their public communication on the basis of examples like the 2005 London transit bombing and the 2006 plot that would have detonated explosives on transatlantic airliners, both of which involved active members of Muslim student associations in Britain.

In order for the department to follow on a lead, conduct a preliminary inquiry, or launch a full investigation, the Handschu guidelines require written authorization from the deputy commissioner of intelligence. An internal committee reviews each investigation to ensure compliance. And every single field intelligence report generated through an investigation is evaluated by a legal unit based in the intelligence division. Undercover investigations begin with leads, and we go where the leads take us. As a matter of police department policy, undercover officers and confidential informants do not enter a mosque unless they are following up on a lead vetted under Handschu.

Similarly, when we have attended a private event organized by a student group, we have done so on the basis of a lead or investigation reviewed and authorized in writing at the highest levels of the department, in keeping with the Handschu protocol.

Let me also say that the NYPD prides itself on its strong relationship with New York City's Muslim community. We hold an annual pre-Ramadan conference with more than 500 religious and community leaders at police headquarters. We assign direct liaisons to the Muslim community and train all of our officers in the diverse cultural and religious traditions of the faith.

We have a Muslim officers society that has over 300 members, and a Muslim advisory council, made up of prominent community leaders that I meet with on a regular basis. They include Daisy Khan, the executive director of the American Society for Muslim Advancement. They provide guidance to the department on all aspects of our public safety mission. Last week they joined the mayor and me at the World Trade Center Memorial to express condolences for the victims of 9/11.

Fortunately, as we have devoted significant resources to counterterrorism, members of the department have not given an inch in our fight against conventional crime.

This brings me to the third and final topic that I want to discuss: the police tactic of stop, question, and frisk.

This is one of a number of tools that we have used to drive crime down by 32 percent since 2001, despite having 6,000 fewer officers in our ranks than we had at that time. We utilize the long-established right of the police to stop and question individuals about whom we have reasonable suspicion. In some cases in which a weapon is suspected, the officer will take the additional step of doing a limited pat-down of the person.

Last year stops by the police resulted in the seizure of more than 8,000 illegal weapons and 819 guns.

I believe that this tactic is lifesaving. It is also lawful and constitutional, as upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1968 in Terry v. Ohio.

Stops are authorized by the New York state criminal procedure law. Every state in the country has a variant of this statute, as does the federal law. This is certainly not a new tactic. It is fundamental to policing.

Critics maintain that the police department stops black and Hispanic New Yorkers in disproportionately high numbers relative to their share of the city's population. They use a thoroughly discredited model of applying census numbers alone to analyze stops by race.

The RAND Corporation, a respected research organization, describes this as the least reliable form of comparison. If we conducted stops according to census data, half of the individuals stopped would be women. It makes absolutely no sense.

Instead, RAND uses the far more reliable benchmark of dictums and witnesses' descriptions of violent crime suspects. On the basis of this standard, it concluded that stops by race comport with crime suspect descriptions.

The number of stops that we conducted last year, 685,000, has also been a point of criticism. But, with roughly 19,600 officers on patrol out of a force of 35,000, this equates to fewer than one stop per officer per week.

Officers must submit a written record of each stop at the end of their tours and the reason for the stop. To be frank, this requirement was carried out inconsistently in the past.

In 2002, in response to a law passed by the city council, we put a system in place to record stops efficiently, with the result that the overall number of reports increased. This reflects, in part, how seriously we take the obligation of reporting.

We realize the sensitivity of every stop. We must preserve the trust and support of the community that we serve and conduct stops with courtesy and professionalism. With that goal in mind, in May the department announced a series of steps to strengthen the oversight and training involved in this tactic.

They include republishing the department's order that specifically prohibits racial profiling and creating an ongoing additional level of training and instruction regarding when and how to conduct lawful stops. We also formed a new strategies and tactics advisory committee made up of prominent community leaders, including Reverend Herbert Daughtry and Reverend Calvin Butts. They provide feedback on the various measures that we use to combat crime and keep the city safe, including stop, question, and frisk.

I am encouraged by the report issued last month by the Civilian Complaint Review Board. Even as reports of stops increased, complaints about police officers have declined to their lowest point in the last five years. That's a good sign. But we know we can always do better.

In a broad sense, the value we place on privacy rights and other constitutional protections is part of what motivates our work. It would be counterproductive in the extreme if we violated those freedoms in the course of our mission to defend New York City.

For this reason, the protection of civil liberties is as important to the department as the protection of the city itself. In the words of the great civil libertarian Justice William Brennan, "the genius of the Constitution rests not in any static meaning it may have had in a world that is dead and gone, but in the adaptability of its great principles to cope with current problems and present needs."

More than a decade after 9/11, New York enjoys the distinction of being the safest big city in America. We all know that wasn't always so. It is also commercially vibrant, culturally diverse, and free. I would argue that the fact that we can claim these successes is due in no small measure to the 50,000 men and women of the New York City Police Department, uniformed and civilian, who have demonstrated initiative and imagination in upholding the law and all of its constitutional guarantees.

I want to express my gratitude to the Carnegie Council for this opportunity to spotlight their exceptional work and for everything that you do to make this city and this world a better place.

Thank you for inviting me today.

QuestionsQUESTION: Susan Gitelson.

Thank you from the individuals here. It means so much to us.

Since we concentrate usually on international policy and you have been active in Interpol and counterterrorism is so important and the people who perpetrated the 9/11 destruction were from abroad—from Saudi Arabia in the main—what do you do about stopping the influence of even religious leaders who say terrible, scurrilous things about others? Tom Friedman has an excellent column about that today. Words can have a devastating effect on people, who then want to act out and destroy others. How do you deal with this on an international basis?

RAY KELLY: I think you just have to be aware of it. Obviously we are concerned about deeds as opposed to words. It is one of the fundamental safeguards we have in our country, the freedom of speech. But we know that the mode of words and speeches can motivate people to do bad things.

We have our ear to the ground, you might say, but we have to really focus on acts, as opposed to speeches or words. That's the world in which we live. I don't know what more we can do, other than to be aware of our surroundings.

As I said in my remarks, we have officers assigned in 11 cities throughout the world. They are in Abu Dhabi; they are in Amman, Jordan; they are in Tel Aviv; they are in Paris, Madrid, London, Toronto, Montreal, Singapore, and the Dominican Republic. They are all there to protect this city. They have their ear to the ground, but they are asking the New York question: What's going on there that can impact New York? What can we learn from what's going on there?

We are doing more than any city in the world, as far as I know, to protect ourselves. But there are no guarantees. There are no guarantees.

Violent rhetoric is just a fact of life. We are going to hear it. It is not going to stop. We simply have to, I think, continue to do what we are doing.

So far, as a result of good work by NYPD people, good work by our federal partners, and sheer luck, we have not been attacked, and we have had 14 plots against the city. So we are going to continue to do what we believe we have to do, continue to do what has been working for us, to protect the city.

QUESTION: Jim Traub, Foreignpolicy.com.

I want to ask you about something else, the debate over the Khalid Sheikh Mohammed trial and whether it should be held in New York in a civilian court as opposed to otherwise. Your recommendations to Mayor Bloomberg about the security issues that would be involved with that played a huge role, I think, in ultimately making the Obama administration change its view from "it should be held in New York in a civilian court" to "no."

Obviously, a lot of people thought that, as a matter of public policy, it was enormously important that he and other accused terrorists be tried in civilian court.

So I want to ask you about the balancing question in your own mind. When you make a recommendation like that, are you also thinking about the questions beyond security—that is, these kinds of public policy equities—given that your own role was so important in determining what is going to happen?

RAY KELLY: Let me tell you what happened in that instance. The Justice Department announced—the attorney general called the mayor, the U.S. attorney here called me on a November morning and said that the trial was going to be held here in New York. We had no previous discussions about that. It was a given that the trial was going to be held here.

What we started to do was an in-depth security assessment. We worked with our federal partners, but, for the most part, we put together a very comprehensive plan to protect the city—obviously the immediate area on Pearl Street, where the trial was going to take place, but other areas in the city as well—over a few weeks' time. We presented that to the Justice Department. They looked at it. They thought it was a very well-done plan.

We said, "We have to do this totally on overtime"—as I said, we are down 6,000 police officers. We were going to have to find the money someplace;—"so, federal government, it will cost us about $200 million a year."

They accepted that. They realized that it's an expensive proposition. So that's what we put forward.

Now, in the meantime, there were lots of political pressures going forward. It wasn't as a result of any recommendation that I made. I said, "We can do it, but we need money to do it. We need people to do it." And it was accepted by the Justice Department.

The reason why the trial was moved I don't think had anything to do with the $200 million, quite frankly. I think it had to do with the political pressures.

Your question was whether or not it should be in the civilian court or a military tribunal. I'm somewhat agnostic about that. They certainly have been successful in civilian court in trying these terrorism cases. The reason it was moved was because of Congress. Congress basically prevented the administration from going forward with the trial in a civilian tribunal.

We could have done it. I have no doubt that we could have done it. This was no sticker-shock approach to scare the federal government off. That's what it cost. They looked at it, they scrubbed the numbers, and they agreed with us. Those are the facts.

QUESTION: James Starkman.

The current issue of Fortune magazine has a rather fascinating article on so-called big data and data mining, which has been used to bring to justice members of the Mexican drug cartel, and there were other illustrations in law enforcement and prevention of crime in which big data and data mining are used. What would it take in terms of sheer dollars for the New York PD to really be up to speed completely on a data-mining installation?

Secondarily, we need you to be the next mayor of the city. (Applause)

RAY KELLY: Thank you.

I'm a big fan of data mining. I would like to do a lot more of it.

The mayor has put in place a project with New York University—it just has gotten off the ground in the last few months—to do a lot more data mining in city government than we have done in the past. But I have been trying to do that for the last few years. It's just difficult for us to get the technology on board, get the right people on board to do it. But I think we—the department—are a treasure trove of information that data-mining experts would have a field day with, and it would help us better protect the city.

To put a price tag on it is difficult to do. Everything is expensive these days. One of the real problems that we have is just the acquisition process in government. It's so difficult and cumbersome. That's why we are always, to a certain extent, a little bit behind the curve as far as cutting-edge technology.

But we just announced, with the mayor, about three weeks ago what I will call a joint venture with Microsoft. We asked Microsoft to help us work with our people.

It's sort of an idea of police officers determining what they need, sitting down with engineers—in this case, Microsoft—and developing something that we call "a domain awareness system." It's sort of one-stop shopping. It is focused right now in Lower Manhattan, but we are looking to migrate it to other areas of the city. Microsoft is going to take it and market it to other cities and other countries throughout the world.

What it does is bring together the cameras that we have—and we have a lot of smart cameras, over 3,000 cameras, which we put algorithms into and have them act basically as alarms—license plate readers —and all of our databases are queried by, let's say, a lead. We have a lead that comes through maybe 911 or some other way. It goes right to that location.

It shows us any cameras that we have within 500 feet. If that lead referred to something that happened three days ago, the cameras show you the pictures from three days ago at 2:00 in the afternoon, we'll say, any license plate readers that are relevant, and every bit of data that we have on that particular lead. Let's say, in the simplest case, it's a car. Every time that car has been stopped or received a summons or whatever, it's all on what we call a workbench.

It's one-stop shopping for government. Microsoft thinks it is very marketable. We will get 30 percent of the revenues generated by this. We estimate that once this is up and running and being sold, it can bring in about $300 million a year to the city coffers.

We are thinking these thoughts. We have been able to get some really top-notch people to come into the department—certainly not for money, because we simply can't pay them—but we are able to get bright young people from some of the top schools in the country—Harvard Law School, other Ivy League schools, and military academies—who are working for us and doing some really outstanding work.

But data mining, to get back to your original question, is something that I think would help us in a very significant way in protecting the city, and we are certainly looking at it.

QUESTION: Don Simmons.

On a different matter, by what percentage would the jail and prison population of New York City be reduced if possession of marijuana were to be decriminalized? Secondly, would you be in favor of that, to free up resources for other purposes?

RAY KELLY: Just mere possession of marijuana—nobody is going to be spending any time in jail for marijuana possession. That's the reality of it. People who are selling marijuana certainly on a big scale, which we have in areas of the city, that's another issue. It definitely generates violence, turf battles, and that sort of thing.

That's a determination for the legislature, if it should be decriminalized. Let the legislature address it. Don't have the police department make de facto on-the-street determinations of whether or not it should be criminalized or not.

Maybe to clear up something, there was this allegation made at a city council hearing that police officers—I mentioned stop and questioning and frisking—were requiring people to empty their pockets. If you have marijuana not in plain sight, it is a violation, it is not a crime. If you have marijuana in view or you are smoking it—generally, that's what it was aimed at—then it's a misdemeanor.

They made the claim that this was happening, that officers were directing individuals to empty their pockets and arresting them for marijuana. We have no way of knowing if that was true or not, because that level of specificity is not in the arrest reports.

I put out a directive saying if in fact that is happening, you can't do it anymore. We put that order out. Marijuana arrests have come down somewhat—maybe as a result of that, maybe not. I thought maybe that might be one of the reasons why the questions were asked, because Mayor Koch and others have written about it.

Nobody is going to jail for marijuana. It's as simple as that. But it is a quality-of-life issue in a lot of neighborhoods. We get a lot of complaints about it. In the abstract, it may be okay, a victimless type of violation. But if it happens in your neighborhood and people are smoking on the corner, some people have a different view of it.

We say let the legislature address it. If it's going to be decriminalized, fine. We enforce the law. We don't want to be put in a position where we de facto write the law.

QUESTION: David Hunt.

Commissioner Kelly, I think your initiative to put liaison officers overseas is absolutely brilliant, to essentially bypass the cumbersome security requirements that the CIA has to pass information. I'm sure this has been a useful tactic.

But do you hear from your men every day? I think you said you had somebody in Oslo. Do you hear from your man in Oslo every day? Has this been a really productive means of gathering intelligence from overseas?

RAY KELLY: We don't have anybody in Oslo. But every one of them has a video conference every day. They check in every day. They give reports of what's going on. It has been useful. For instance, in 2005, when the London train bombings took place and the bus bombing, I was on the phone with our liaison officer literally within moments after it happened, because he was in the command center of the London police.

It's funny. Ian Blair, who was the superintendent of the Metropolitan Police at the time, tells the story that he was writing a speech that morning and he did not want to be disturbed. With sort of typical British aplomb, they didn't notify him. He's sitting in there for two hours writing his speech. He didn't know about the bombs. I knew about it way before he did.

Why did we want to know about it? We knew that it was going to be a huge story—concern about the comfort level of the people riding the subways, that sort of thing. We were able to put additional resources at subway stations throughout the city, and we did it quickly.

Yesterday I saw a copy of the federal government's report on the London train bombings. It came out in August of this year. I didn't see it until yesterday. Somebody brought it to my attention. But seven years after the events took place, we get a copy of the report. In the meantime, I'm getting a report from our person there within minutes after it happened.

We simply can't wait for that type of ponderous federal government response. I've been in the federal government. I know a little bit about it.

What it does is to give us immediate information. It also gives us the ability to respond to other places in the world where there is a terrorist event. Let me give you another example.

When the attacks took place in Mumbai, we were monitoring Twitter, like the rest of the world, getting a lot of information. We sent three of our liaisons—we don't have anybody in Mumbai—to Mumbai. They were there, I think, within a day or so.

We had gone to Mumbai a year-and-a-half before, because seven commuter trains had been attacked in Mumbai. So we had a relationship with the police there. We sent the same person and two other liaison officers from other locations. One was from Jordan and the other two were from Singapore and one other location.

We got real-time, granular information. We went to the Chabad House that was attacked. As a result of what we learned there, our officers did a 75-page report that we had in less than a week. We brought in the security directors of many of the major corporations.

By the way, we have something called NYPD Shield, which has 11,000 security people as members of it. It's an umbrella organization. It's a BlackBerry-type relationship.

We gave that report to the FBI. We had, as I say, about 500 of them in the audience talking to our people in Mumbai on a telephone linkup. Again, this is in a week's time.

That afternoon we had a tabletop exercise with my executives. We watched television from the conference room, where they roughly simulated the attacks and what happened in Mumbai. We watched it. We were working on a roughly similar scenario.

Information that we gleaned from Mumbai made us increase the number of heavy weapons people that we have in the department. We have a corps of about 400 emergency service officers, but we were concerned about a protracted hostage-taking type of situation. So we embarked on a training regimen. We have another 250 officers that in an emergency could respond and do that sort of work.

What we also did was to go and videotape the insides of all the major hotels in the city. The average officer is not going into one of these hotels, but clearly if you are assigned to Midtown Manhattan, we would like you to have some understanding of what happens in some of these big hotels. We use that now as a training program for officers. When they go to the precinct, we use it as a refresher.

That all came out of the visit that we had, quickly, from our liaison officers. We were the first to determine that semi-automatic weapons were used, not automatic weapons. Our people went right to the train station in Mumbai. There were no marks on the wall. You know, when you use an automatic weapon, it tends to rise, that sort of thing? That's the type of granular information that we had, and we had it quickly.

So we want to react quickly. We want to use those liaison officers to go to the scene, get immediate information. It has been very helpful in a variety of ways—again, funded by the Police Foundation. We are not using tax levy funds to pay their expenses. Their expenses are paid by the Foundation.

So we find it very, very useful and are going to continue it.

We are going to put them in places where there is a hospitable climate. The difference in this program from federal programs is that they are embedded with the local police. They're not sitting in the U.S. Embassy—which is of value, granted. But this is a sort of cop-to-cop relationship that we find every effective.

QUESTION: Anthony Faillace.

I have two questions. First, London has a very well-known system of having cameras in public places, such that they can monitor activity and use that for crime stopping. How valuable would that be here in New York in helping the police officers' efforts?

Secondly, how important is having an extensive DNA database in the solving of crimes, and what are some ways that that database could be enhanced without violating people's civil liberties?

RAY KELLY: Paul Browne, who is over here with me—we visited London in May and we looked at their system. They certainly have a lot more cameras than we have.

They're terrific, by the way, at sharing information. We have a great relationship with the Metropolitan Police.

But their cameras are a lot less sophisticated than the ones that we have. As I said before, we're able to put algorithms into the cameras and have them work as alarms. If a package is put down and left for, let's say, three minutes, that sets off an alarm for us. If a car goes the wrong way on a street, that sets off an alarm. We are, in that respect, ahead of them. In terms of gross numbers, they have a lot more than we have.

What we have done is homogenized, if you will. We have private sector cameras, public sector cameras. A lot of the private sector cameras are a lot of different networks and different qualities, that sort of thing. We have been able, with great effort, to get these private feeds and have them all come in, in one system, so that we can very quickly go to those accounts.

We have asked the federal government for more money for the cameras. The initial grant was $10 million for what we call Argus cameras, which are throughout the city.

We have a Lower Manhattan security initiative, which is the 1.7 square miles south of Canal Street. That's where we have about 2,500 cameras, in that location. That's where the bulk of them are. What we're in the process of doing is setting up a similar program in Midtown Manhattan.

Cameras are very valuable. When a crime happens, that's what officers do immediately—look to see where the cameras are. It has been very, very helpful. So we in the organization are major proponents of cameras. We want more cameras and more money for them.

But I think our cameras are—the quality is maybe a step ahead of what they have in London.

As far as the DNA database, we're all for it. The issue has been when do you collect it, for what crimes do you collect it. When people are arrested, their fingerprints are taken. I would say that DNA should be roughly akin to fingerprints. But there is significant resistance to that by the Innocence Project and people of like minds. They think that DNA can be planted, that people can be falsely accused, that sort of thing.

There's an issue now ongoing as to whether or not you should wait for people convicted of felonies. That's basically where it stands now.

But it has been very helpful to us. Bob Morgenthau, when he was district attorney a few years ago, put in a program where we can, in sex crimes, indict the DNA and then find the person, which is terrific.

So DNA is helpful. We hope it expands. That's sort of where the discussion is now as to who gives it up.

QUESTION: Richard Valcourt, International Journal of Intelligence.

Back to the quality-of-life issue that you mentioned, we have seen a lot more, I think, homelessness and aggressive panhandling on the streets and on the subway trains and so on. To what extent has the "broken windows" policing, so to speak, been decreased in recent years?

RAY KELLY: It hasn't, hopefully. The notion that you can arrest everybody is just—you couldn't possibly do it. That was the concept. But zero tolerance is impossible to enforce. It never was enforced.

But clearly we don't tolerate it. We are giving out summonses and arresting people all the time. As I say, we arrest 400,000 people a year. We give out 500,000 summonses. We have 6,000 fewer officers than we had. So the actual ability to confront someone who is doing this has been lessened, but certainly not the desire to do that.

I go to other cities. I see a lot more people on the streets and homelessness in other cities than I see here.

I would like to hear about it where you are seeing it. Do you think it's on the subways? Where do you see this happening?

QUESTIONER: Certainly on the trains, and certainly in the early evening, or even later evening, in the various doorways in Midtown. They are more aggressive. For a while, it was a little more passive. Now they come out, and increasingly so—certainly on the trains.

RAY KELLY: Okay. It's obviously something that we try to address. Let me see what we're doing with it right now. I'll talk to people.

We have over 2,000 police officers assigned to the transit system. In 1990, there were 50 crimes a day, index crimes a day, on the system. Now we have about seven crimes a day on the system. Five million people use it a day.

One of the recent upticks that we have seen is the theft of iPhones, tech equipment. It's something that we are trying to address in a variety of ways. We have decoy operations on the subways. We are putting up posters for people to protect their iPhones. What happens is, these phones have become entertainment centers. It's no longer just a phone. People get almost mesmerized by it, and they take it out of their hands and run out the door. We have seen an uptick with that.

But I'm glad you told me about it. Thank you.

QUESTION: Arlette Laurent.

You talked about video cameras. I wonder, how long do you keep the data in the video cameras throughout the city? Thank you.

RAY KELLY: We keep our data for 30 days and then it is automatically erased unless it's being used for an investigation.

We have on our website what I would submit is a cutting-edge privacy policy and document. It was put together largely by Jessica Tisch, who works for us. She has done a terrific job. She's very much involved in our Lower Manhattan security initiative. Jessica is a Harvard Law graduate and worked with privacy advocates to construct this privacy policy. It's on our website. You can go and read it.

But absent an investigation, the cameras automatically are erased after 30 days.

QUESTION: John Richardson.

You have talked a lot about data, and obviously collecting data is important for the police, securities, weather, IRS, all that sort of stuff. My question is—maybe you have answered it, but I'm just trying to clarify—there's data, there's collecting data, and making decisions based on that. What I'm interested in is the theoretical, and maybe the practical, sides of trying to incorporate some concept of randomness in what you do.

On the intellectual level, can people work that into your systems? Obviously you don't want to have somebody, necessarily, sitting in the middle of the Sahara Desert for six months, thousands of miles from anybody. But just the notion of randomness—because if it can be proven to work somehow, the political side of that is that eventually you may have less flak from people saying that you are racially profiling or you are doing something else.

RAY KELLY: I think I understand what you mean. We don't have the resources to do that. We have to focus on leads.

There is this notion that somehow we are able to look at the universe. We can't. We have limited resources, as I say. Again, we're down 6,000 police officers. We have to focus on what we're doing.

We have a bag-search regimen in the subway system. We're the only subway system that does this.

We're the second biggest subway system in the world, by the way. As I say, 5 million people travel the system.

After the second attempt in London in July of 2005, we put in a bag-search regimen in the subway—obviously not every station. We move it around every day.

They use a scheme that is similar to, say, DWI, driving while intoxicated, checkpoints. A sergeant will go with the team and, based on the traffic, he'll say, "We are going to stop every fifth person with a bag," or every tenth person with a bag. They set that up, getting to your point of randomness.

They will use airport-type testing of equipment. They stop someone with a bag, tell them what's going to happen. They will use the swab on it. Then it takes less than a minute, and people go on their way. That's what we also do with DWI checkpoints. You need some sort of scheme, you might say, or pattern, to follow, rather than just randomly pick out people.

JOANNE MYERS: On behalf of the Carnegie Council and everyone here, I want to say thank you for allowing us to sleep better at night and also for taking the time out from your busy schedule to talk to us. It's a real honor.

RAY KELLY: Thanks a lot.