Never at a loss for words, the inimitable, erudite, and very funny Simon Schama free-associates his way through Jewish history: the Old Testament, Jewish dancing masters in 16th century Italy, Passover recipes, the future of Israel--it's all here, and more.

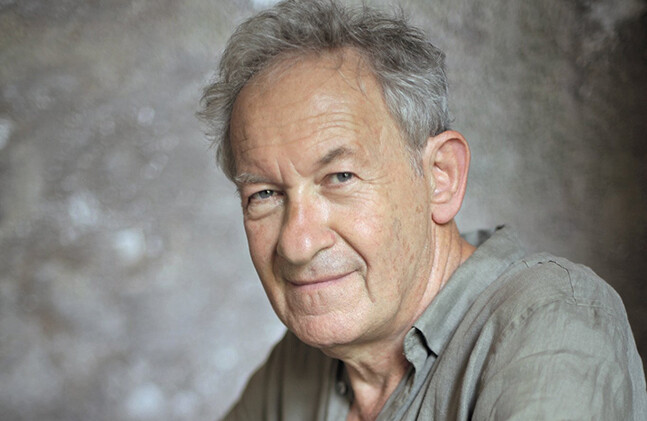

JOANNE MYERS: Good morning. I'm Joanne Myers, and on behalf of the Carnegie Council, I would like to thank you for joining us as we welcome one of the most prolific, free-thinking, imaginative, talented, energetic, and original minds to grace this podium, the prize-winning author and Emmy Award-winner historian. And, of course, I'm speaking about Simon Schama.

This time, Professor Schama is here to discuss his latest achievement, The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words (1000 BCE-1492 AD), which some have said is his best work to date. His earlier talks on The American Future and the interesting essays found in Scribble, Scribble, Scribble can be accessed by visiting our website at www.carnegiecouncil.org.

There are many ways one could choose to describe our guest, but the one thing that can't be said is that he is afraid to tackle broad and challenging subjects, as his own studies have been remarkably diverse, whether he is writing about the French Revolution, the slave trade, or telling us stories about the great Dutch painters. Professor Schama does what he always does best, which is to convey both expertise and a real, personal, human passion for his subject.

The Story of the Jews is the first of two volumes which greatly expands on the story told by the five-part television documentary which aired on the BBC and was recently shown on PBS, captivating viewers on both sides of the Atlantic. The second volume, which will be published this fall, takes us up to the present day, and it bears a rather more somber subtitle, When Words Fail (1492-Present).

Now, writing about Jewish history can be a daunting task, even if you are as renowned as Simon Schama. Knowing that the endurance of the Jewish people has been in the telling and retelling of their story, the question was, where does the story of the Jews begin? This seemingly simply question can be much more elusive than might appear.

For Professor Schama, his telling of the story of the Jews commences around the time Jews began to be thought of by scholars as a unified people and ends with the Spanish Inquisition and the Jews' expulsion from Spain. In between, the author pivots among civilizations, depicting Jewish life in the ancient Near East and the Roman and Hellenistic worlds, including descriptions about how Jews coalesced with early Christians and Muslims. His narrative stresses that Jews have not been, as is often imagined, a culture apart, as their culture has busily intermingled with others.

He writes, "What makes the story at once particular and universal is a shared inheritance of Jews and non-Jews alike, an account of our common humanity in all its splendor and wretchedness, repeated tribulation and infinite creativity."

If you have even the slightest curiosity about history, culture, or civilization, I'm confident that you will devour this book with the enthusiasm and fascination it rightly deserves.

I think you know by now that I am as enamored of our guest as much as the rest of you, who find Simon's enthusiasm for exploring the past so infectious. I could go on, but there is a lot of ground to cover—thousands of years of history, to be exact. So I think we should get started.

Please join me in giving a warm welcome to our guest today, Simon Schama.

RemarksSIMON SCHAMA: Thanks so much, Joanne.

Yes, 3,000 years in five hours of television. Let's do it in half an hour, shall we? It's like my favorite Monty Python sketch, which was Marcel Proust in a minute and a half, really, or the exceptionally abbreviated Shakespeare company. They were really wonderful.

It's true that part of the thrust of what I've been doing in this book is actually to stress some of the things that connect Jews and non-Jews. My own wishful thinking is for a kind of cultural pluralism, wet, centrist liberal as I am. But you can take it too far. So I'm very relieved, since I know about the threats worse than civilization that is the cronut, that we don't yet have the cragel here, although I think it has been invented.

You have no idea—all of you need to get out more, actually. You don't know what I'm talking about, do you? The cronut is the horrible mutant between the croissant and the donut. Someone has invented a croissant-bagel, which is called the cragel, which sounds suspiciously Yiddish anyway.

There are lots of words—have you noticed this or is this just the effects of me spending too much time with Jews?—all sorts of words which are, in fact, not Yiddish, but you think obviously must be, like "moist," for example. I was in Scotland not very long ago and everybody seemed to be called Hamish. And I thought, there can't be that many Jews around here.

This has been an extraordinary experience. I will again start with a sort of shameless promo moment. As Joanne very kindly said, this has been my voyage in the past—I hope you caught the television series. Actually, in some sense, the last three programs are three stages in a kind of single tragic opera, which is about the emergence of the possibility of Jews living as citizens, free citizens, of countries, and in some places—pretty much only the United States—succeeding, and in other places, catastrophically failing.

On the other hand, three solid hours of The Story of the Jews Tuesday night is almost too many Jews even for me, actually. It's on lots of repeats.

Once again, shameless promo time. The DVD—I don't have them here to sell you, but I just want to alert you to the fact that what those of you who will have seen the PBS series saw, for which—wonderful Dan is here. Dan was one of our wonderful godfathers, without whom the series wouldn't have happened. But in order to thank Dan, which is right and proper, and many others of our very kind and generous patrons—Dan Rose—we had to cut the programs by about seven or eight minutes. So if you want, actually, the full, uncut program—for example, Spinoza, an incredibly important figure in the relationship between Jews and the modern world. If you want to say, was there any Jew who made a profound impact on the way the modern world was going to be shaped, other than the familiar trio of Marx, Einstein, and Freud, it would be Baruch Benedito Benedict Spinoza. That we had to lose.

So if you want to see the whole brick, the DVD is a good way to do it, and the book is an even better way to do it. One thing you have to do with a television hour, if it's going to be good television, if it's going to do two things that history, actually, demanded—to which I'm going to come in just a second, you'll be relieved—from Herodotus onwards, it's to launch an inquiry through the means of storytelling, launch an inquiry through narrative. You have to obey certain really ferociously constrained rules of the narrative arc in television. You don't have to do that in a book, for better or worse, which is why, to my publisher's horror, it's two volumes rather than one. So I hope you'll explore, it being Passover, all versions of this.

So why did I do it? Why did I commit this extraordinary act of hubris-laden temerity and tackle something? It's for the following reasons. There are personal reasons, which I'll talk about now, to do with my engagement with history since I was a child, really, but certainly over the last 50 years, half-century, of teaching and writing about it. Then there are, I think, more recent civic reasons, not to be too sanctimonious about it, but which have become urgent, and surprisingly urgent, and are reasons that are not very Carnegie Council reasons, not just about the Jews in the world, but about the way the world is.

Personal reasons first. I was born in 1945, the night of the Dresden raids. It wasn't entirely a one-way process, because V-2 rockets were landing heavily in London—in fact, demolished much of the street on which I was born, but not the clinic in which I saw the world. Somehow, for better or worse, I was spared.

But I grew up in a very damaged world—a very cheerful world, but it was London and Britain in the late 1940s. I guess my sense of where I was in history began very early on, pretty much at the time I started to learn Hebrew, about five years old. In the late 1940s and early 1950s one necessarily grew up in, as I say, a very wounded, hurt, physically wrecked world. My dad used to take me around the kind of blackened ruins of the city in East London where he worked. I would irrepressibly kick footballs dangerously around bomb sites to be hauled off by—"Oy, you, lad"—policemen.

I had the sense even then—I'm sure I did—that history simultaneously was, in the very austere, dark, cramped world of post-war Britain, a romance. It was where you went to for the color of time, as Macaulay, great ancestor of those of us who seek to educate while trying to entertain as well, felt it was. So I absolutely plunged into historical novels, particularly Walter Scott. I may be the only person ever, really, other than the author, to have read the historical novels of Arthur Conan Doyle, (I know several of you are going to rise to your feet and say, "No. I read them.") Stevenson, so on. And I also read the Bible, of course. I read the Bible for its most romantically swashbuckling—I couldn't get enough of obscure kings beating the bejesus—that's not quite right for the Old Testament, is it?—out of other obscure kings.

This is not meant to be disrespectful. I was very proud of the Old Testament for being so full of blood and thunder. I always felt that the New Testament was a little on the milquetoast side by comparison, actually. It had this sense of sweetness which I as an 8-year-old was so not interested in, really, whereas Cain's murder of Abel, Jacob deceiving Esau, the cringing coward Jonah saying, "Why me?" I loved the moment—I still do love it—when we read it in the afternoon service in Yom Kippur, Day of Atonement, where Jonah—it's horribly Jewish—complains to God. He's a great kvetcher, as is Job, but Job has a lot more to be a kvetch about. Jonah has had this long weekend in the belly of "the great fish," as it is in Hebrew, dag gadol, not a whale. Then he arrives at Nineveh to deliver the bad news that they're about to be zeroed out as a result of manifold transgressions, only to discover that Jehovah, as is his wont, changed his mind. Jonah is very put out by this and basically says, "Can't we just have a little bit of destruction? I've gone to all this trouble."

I remember loving that. It sounded like someone I knew at synagogue or something and is the genius, again not to be overly digressive—moi?—it is the genius of the Bible writers, unlike the writers—I suppose, actually, Homer is another case in point where you do actually have the gods discoursing among themselves as if they were meeting at a particularly bitchy cocktail party half the time. That's quite true.

But the genius of the Bible writers is to make their world very impure, to sort of have recognizable human types, including Moses, at all times.

I was aware, to go back to the 1940s and 1950s, that these two histories were histories of damaged cultures, cultures that had not—neither British nor Jewish—been annihilated. Indeed, my father thought there was some sort of providential connection between them.

On his bookshelf—I do remember this very vividly—side by side were the four volumes of Churchill's A History of the English-Speaking Peoples and Chaim Weizmann's Trial and Error. Of course, Churchill was a kind of covert Zionist. He's one of the people without whom the Balfour Declaration wouldn't have happened. My father felt, quite rightly—and if you're still in any doubt—and I'm sure you're not—Churchill's management of the cabinet, the full cabinet, in May 1940, John Lukacs's book, Five Days in London: May 1940—it's very short, and it must still be in print—is an absolutely wonderful, thrilling story about how it could easily have gone Halifax's way and there would be have been a disgusting, squalid negotiated peace with Mussolini in 1940.

So my father was in no doubt at all. In some sense, Churchill was the difference between our family surviving the war and some of my mother's mother's family, the Naumanns [phonetic], in Vienna, not. There was something functional, not just ornamental, about the history of both the Jews and the British that made them sort of dig in their heels in various ways, resist annihilation, or come out of the ashes of annihilation determined to protect and endure.

There is this wonderful speech that Churchill makes. It's not often reported, but it's reported by Hugh Dalton, in the larger cabinet that he has cleverly assembled to repudiate any possibility of any tentative negotiation with the Axis. It's kind of like "we'll fight them on the beaches," and so on, but it's much more violent, actually. Churchill says, "I would rather die on the ground choking in my own blood than contemplate a surrender." It's quite a wonderful moment.

That, my father thought, was, in some sense, like Old Testament—prophetic, voracious.

So there was a sense, as I say, which I got very early on, that history is not just a stroll down memory lane; it's not just a kind of ornamental exercise in escapism. There's nothing wrong, I guess, with Downton Abbey. You all love it, I'm sure. You have to understand, I'm a 1960s kid, at another level. I grew up with that. I'm now on record as saying, "Burn down country houses," rather than be surrounded by their peculiarly pretentious form of snobbery and obsequiousness. But heaven forbid I should spoil your pleasure in that. And I'm sure I won't. But I have been known, for my imprecations about this, to be the "Downton Rabbi," actually, which I'm happy to be.

History is essentially, as it was designed, not just by the Jewish Bible writers and Josephus and the great tradition onwards, but by the Greeks as well in the Western tradition, as something that is really written against consolation, which is against self-congratulation. Thucydides, our first great critical master, was himself a protagonist in the events that he describes, wasn't he? He was a general who had been fired for incompetent performance on the northern front in the Peloponnesian Wars.

But he did not write the history simply as sour grapes. Even though he was very critical of Herodotus's pussyfooting around with mythology and not sorting it out from established facts, he did take on Herodotus's sense of what the Greek word historia is, which means, simultaneously—very Carnegie Council—critical analysis in the form of storytelling, as I've already said.

That's what Thucydides does. He designs his great story—and this is why I always resent the fact that when undergraduates at American colleges, however well intentioned, only read Pericles's famous funeral oration to discover why one should die for one's democratic country, because that does sound rather like a kind of Athenian chest beating, even in a funeral mode. But the great arc, the great narrative arc, of someone who is a miraculous, almost cinematic storyteller is the expedition to Syracuse at the end of the book, where the whole work is designed for a moment of catastrophic self-knowledge, when the naval expedition to Sicily goes disastrously wrong. So the great debates before that between Nicias and Alcibiades, between the sort of Henry Kissinger and Donald Rumsfeld, respectively, is incredibly important in this respect.

History necessarily nourishes our sense of self-criticism. Great history is designed not to be a genealogy of the wonderfulness of us now. It's terrific that there are all these histories of the Founding Fathers so that we have the sense that once all the great patriarchs of our American democracy were wise, white, virtuous, brilliant, articulate, and so on. And look at us now. That's fine, particularly if they look at us now.

By the way, actually, since I'm in such an august company, what are we going to do about the Supreme Court, who are campaigning to replace democracy with plutocracy as of yesterday. This is not really my brief, but then again, why not? This is really the most shocking—this country, which I love deeply, was founded against the plutocratic oligarchy of Hanoverian England. We've become Hanoverian England, where money bought you power. It doesn't always succeed in the moment. So I want you all to feel a sense of virtuous democratic rage about this, because we're losing democracy, absolutely.

Let me return. It's amazing that going back to the Jews is a safer place to be. I'll do that.

History is not meant to be, as I say, a sort of safe place to be. It is meant to ask deep and profound questions.

This is something I felt I had to do. I wrote a Jewish history book and published it many years ago, a book about the French Rothschilds and the land of Israel. I had a tempestuous relationship with Lord Rothschild, Victor, one of the most brilliant and difficult people I've ever known—some of you, I'm sure, knew him—who famously, when I was late delivering a chapter or something, slammed his hand on the table, after having beguiled me with a glass of Mouton Rothschild, and said, "Do you know what our motto is, Simon?"

I said I couldn't remember it. He said, "Service. And by god, we get it." He knew what he meant.

The reason I took the sense, actually, of Jewish history being urgently needed is the following thing. It arises from one of the things I hope I've already made clear. It's actually very important for our children and our grandchildren. I now speak as a new grandfather. I love joining that club.

Actually, since I'm on a mad, kind of fanatical campaign to mobilize you to do certain things, to turn you all into 1960s protesters, one thing we could all do for our children is to mount a campaign to abolish the phrase "social studies" at school, which instantly declares history to be dull and worthy in a kind of unexamined, bombastic, hollow, vacuous way. History ought not to be the discipline that dare not speak its name. History is thrilling, exciting. It's something that our kids should enjoy.

Here's another reason, before I come on to the contemporary civic reason why I did this. Many of you will know that Jewish history has undergone the most extraordinary transformation since my august and extraordinary predecessor Salo Baron wrote his 18-volume history, which is absolutely the last word. In the 1980s it was completed—an extraordinary masterwork.

But all sorts of things have happened since Baron died, actually. The archaeology has changed. Jewish art history, which used to be thought to be an oxymoron—we now know the world of images, you will have noticed from the television—and I spend a lot of time with them—is formative for Judaism. It's not only a complete misapprehension to think that the Second Commandment was a prohibition against painting, for example, or mosaics—it wasn't. It was always in the first half-millennium, with the existence of the synagogue, that the Second Commandment was intended as a prohibition against sculpture, against pagan three-dimensional images.

All these things have happened. Jewish history has never been more fervent, more alive. But it often doesn't take the form of a sustained, continuous narrative. Narratives, whether in high school or middle school, are the way in which our children and all generations are wired to ask questions. That's what Herodotus, Thucydides got right. We are profoundly wired to ask ourselves questions, provided it comes in the form of making the past live—as W. H. Auden said, enable us to break bread with the dead, to see that those who have gone before us have something materially urgent with which to instruct us about our own predicaments. It's not like drawing a kind of simple template, simple solutions for calamity—how can we prevent the Holocaust from happening again? Historical calamities happen regularly in their own particular way.

Actually, to simply idly and loosely draw Holocaust analogies whenever there's a rising tide of ugliness, as there inevitably is, is in some way a lazy thing to do, even if it means to be a reverent thing to do, because it stops us from actually looking at the particular problems and troubles and uglinesses of another round of difficulty.

I'd be happy to answer questions about that. Everybody always asks me about European anti-Semitism now. It's a good and proper question.

Here's the final reason, which is deep, about why I thought I had to do this, other than the fact that it would seem crazy not to respond positively to an invitation from the BBC. Anshel Pfeffer, the wonderful writer and critic for Haaretz newspaper, very sweetly reviewed, in a generous way, the television series and said, "Simon Schama has done this terrible thing, because he has actually robbed Israelis and Jews generally now of the accusation that the BBC is profoundly and incorrigibly anti-Semitic."

It was their idea to do this, and they never leant on me for anything, really. I have only praise. Only public television, in this country and the BBC, is prepared to do documentaries—all praise to them—at this very high-end level.

Here's the thing. Other than the death of the planet, of which we have had yesterday and the day before profoundly upsetting news about the speed at which it's going on—other than the death of the planet and its ecology, the most extraordinarily intractable problem facing the world, whether it costs 120,000 lives in Syria, whether it puts huge parts of Africa, from Uganda to Nigeria, in a state of terror, is the extreme difficulty which communities of belief or national tribes, as they so define themselves, have in sharing the same living space without the obligation to kill each other, or at least to oppress and persecute each other.

Again, fast-forward. Sorry about all this sort of biography. When I was a kid growing up in school in the 1960s, I remember our history teacher, who bore a weird resemblance to Voltaire, or particularly to Houdon's bust of Voltaire, and therefore was blessed with a kind of sunshiny Enlightenment optimism, which you saw I was a faithful apostle of in the Moses Mendelssohn sequence in the program, said, "Well, boys, we don't know what the rest of the 20th century," this being about 1958 or so when he said this, "has in store for us." I'll never forget this. "But," he said, "one thing we know for sure is that organized religion and nationalism will not be a problem." So much for prophetic powers.

But, of course, many of you remember, in the long-shadowed Second World War, we thought, in particular, nationalist hysterics, the sort of hysteria about borders—the sort of thing that happened in the disintegration of Yugoslavia, that's still happening in Russia, Ukraine, wherever you look—would not really be something that would be among the most profoundly intransigent problems we have to deal with.

Now, the Jews have something to say about this problem, of course. It's not that the Jews have suffered from this difficulty of finding a living space with which to share with people who don't necessarily have the same religion and the same traditions. Of course, there are other peoples and cultures—Armenians, South Asians, Indians, Muslims in East Africa, Chinese in Malaysia and Singapore, wherever you look. But the Jews have been sort of unique, perhaps, in suffering from this issue most acutely, most relentlessly, and, of course, for many, many millennia, not having had somewhere to go to that they could call their own—the famous formula begun to Leo Pinsker in the 1880s on auto-emancipation and sustained by Herzl until the foundation of Israel—and therefore have been, as Jews were in the 1930s, the most abandoned people of all.

I said, for those of you who didn't catch it, that it's not what the Nazis did to the Jews that made the moral case for Israel, and makes it; it's what everybody else failed to do. It was exactly at the moment of most acute need that immigration doors were slammed down in the United States and in Britain and pretty much everywhere else, unless you happened to be heading for the Dominican Republic or Shanghai, amazingly, a story that I'm writing about in Volume 2 that I wanted to talk about.

So there is this sense in which Jews have something to say. It raises what is to be said, the profound issues that Joanne alluded to of whether or not Judaism is sustained by a sense of necessary separateness or whether or not Judaism has equally been sustained by an endlessly reborn optimism about connections. We're all sitting here in New York, in Manhattan. We can't live our lives as American Jews and say it couldn't happen anywhere, because, goodness, this is the place where it did happen. And it did happen, to a large extent, in Britain as well.

I actually start my story, at the beginning of Volume 1, not with a kind of Abrahamic revelation, because we'll never know if any such thing ever happened, but with a documented history of Jews living among people who weren't Jews. Did they have sorrows and problems? They most certainly did among the Egyptians and this extraordinary colony of mercenary soldiers in the Upper Nile, which is a really wonderful place, if Egypt ever calms down and you want to go back to Aswan. The guides take you from Luxor to Aswan, and most of them miss out on the great, beautiful island, Elephantine.

Anybody been there? Okay, you know. When were you there, may I ask?

PARTICIPANT: 1978.

SIMON SCHAMA: You have to go back, because the excavation that was carried out in the 1990s is extraordinary. What we have is really a kind of mixed Jewish-Syrian-Egyptian town, with walls and streets.

Sometimes you have to resist this because history is a foreign country and you are essentially trying to communicate with ghosts, even if you are trying to break bread with them, as I have said. But there are moments when you just time-travel like that. It's a bit like Doctor Who. I could see those Elephantine Jewish teenagers up to no good lurking in the alleys, and I was one of them, really, in the year 450 BC. It is the most extraordinary place.

So I wanted to begin with something in which there were possibilities. The Jews built their own temple in Elephantine, in violation of all the Jerusalem rules laid down by Ezra, Nehemiah, and the Jerusalem high priest establishment, temple establishment.

As I say, I kept on correcting, both in television and also for my happiness being a sort of Anglo-American Jew as well—I kept on correcting for kind of liberal complacency, because there are a lot of places where the experiment of living together didn't work out. But I did once say, wherever you look through Jewish history, there is this extraordinary sense that Jews have never been separated unless they have been forced to be separate.

Even in something like the Venice Ghetto, which was founded in 1516, the Venice Ghetto, unlike the Roman Ghetto, which was a truly grim place in its first two and a half centuries, until the French Revolution—the Venice Ghetto—the doors and bridges were shut and locked—that was not good—at dusk. But during the day, people came and went freely. Gentiles, Christians, came into the ghetto to work as artisans and dyers and tanners, and work in the many artisanal workshops in the ghetto, and Jews went out—guess what—as doctors, of course. But also, rather wonderfully, the thing the Jews were famous for, everybody, was the dancing masters. The Jerome Robbins of 16th-century Italy was a man called Jacchino Massarano, who we know quite a lot about.

Showbiz, by the way, does not begin with Mr. Berlin and company. It begins with a wonderful man—he features in Volume 2, so this is a teaser for that—called Leone de' Sommi, who lived mostly in Mantua and had a group of professional actors. He wrote a rather funny Hebrew comedy, the first secular Hebrew comedy, A Comedy of Betrothal, so-called. But he had this extraordinary group of actors who performed before the courts, the town. He wrote the first book on stagecraft, on makeup, on lighting, on language. He was altogether a remarkable and extraordinary figure.

So the Venice Ghetto was not as hermetically sealed at all. The first time we know that's documented where Christians came to see the Purim spiel, Purim play, is 1531, where troops of patricians came into the ghetto to see it. That's an example of, really—and another wonderful man called Abramino dall'Arpa, who was the great harpist of Venice and Mantua and Ferrara, is a music tutor to none other than Isabella d'Este in Ferrara.

This fertile back-and-forth—when catastrophe happens, Jews, since we're a suitcase-ready religion and culture, found another place to establish themselves, not in a kind of hermetically sealed-off way. In 19th-century Germany, we can sort of hear the drumbeats of disaster a bit, certainly after Wagner publishes his poisonous attack on Jewish music in 1850.

But it doesn't do to sort of downplay the astonishing success that Moses Mendelssohn's dream that you could be a Jew and a German with equal ardor actually had, what German Jews, two generations back in the ghettos of little German towns, achieved by way of entering the professions, science, the gymnasium, legal industry, dominating publishing. The whole thing is as astounding as any journey that a minority culture has taken, really, into the main cultural bloodstream of the nation in which it lives.

And the question in the Middle East, of course, actually now at its most tragic, because all of this was the possibility of a shared life—or the necessity of a safe, separate life is another way of describing, I guess, the argument that Tel Aviv—this is a grotesque simplification—has for Jerusalem or the argument that half of all Israel that wants there to be some sort of, not starry-eyed, utopian, loving honeymoon relationship with the Palestinians, but some sense at least of sharing the same larger world side by side as neighbors of some sort, and those, like Naftali Bennett and his like, who believe only in a fortressed Jewish existence because of what happened to them—of course, if there is even going to be neighborliness, then there has to be neighborliness based on a sense of security.

A Palestinian whom I know quite well said to me once, "We both actually are mirror images, as we have been for a long, long time, the better or worse of each other, and we're dealing with the same problems. I deal with my religious fanatics and the side of my people who want to have nothing ever to do with Jews, and Israelis have to deal, some of my friends, with people who never want to have any kind of . . ." The fact is, those of you who know Israel very well know that every single day, despite the difficulties and the torments and the sorrows and chagrin, even as we speak, made no easier in relationship between Israelis and Palestinians, there are day-to-day relationships wherever you look that do go on—stricken with many daily ordeals, but in businesses, for example, in sharing of water resources, in science and medicine.

I was at the opening of the Polonsky Institute, part of the Van Leer Institute. The wonderful Leonard Polonsky and Georgette Bennett created it as a kind of Princeton Institute for Advanced Studies in Jerusalem. I gave a lecture, partly about Martin Buber, who, of course, is a kind of lodestar of innocent if ultimately unrealistic virtue for me. I'd say, quite quietly, a quarter of the audience were Palestinians.

I refuse to believe it's an impossible thing. As I said, it's no good, because of our history, saying that if we opt, to some extent, for connection rather than separateness, it is going to be easy or it's going to be a love story. It never is. The legends of Jewish-Muslim coexistence in Muslim Spain—this, too, was broken by massacre and violence and misery and horror. There were anti-Semitic riots in the middle of 19th-century Germany, the Hep-Hep riots.

So it's never without strain and stress and sorrow. But it's also never without hope and fruitfulness and creativity.

Before I sound as though I'm turning into a slightly wetter, more liberal version of my friend Jonathan Sacks, I'm going to stop.

JOANNE MYERS: I don't think anyone free-associates so brilliantly as you do. You have touched on so many different issues, and I'm sure it raises many questions. I guess you'll take questions on anything, right?

SIMON SCHAMA: Of course.

Oh, I do have something very urgent and important to say. How many Sephardim in this room? Whoa! One.

What are Sephardim? That's from the Spanish Eastern/Oriental tradition, actually.

Our family had a period in Romania where we hobnobbed with the Ashkenazim, so we call ourselves Sephardi trash.

What Sephardim do—I will put the recipe online for everybody—the real difference in Sephardim—and never mind about Ladino—is, Passover is coming up, everybody. The real charoset is cooked. This will shock you. See, it really has. What I do is actually provide for the hardcore Litvaks and Galitzianers around there, the horrible Manischewitz and almond and cinnamon stuff that you do—I'm sure fantastic. Or you can go to Claudia Roden's wonderful Jewish cooking

Charoset is in the Sephardic tradition—as you would expect, you can use apples and pears. You cook it in a little white wine, if you want, but it should be—orange juice is a great thing, freshly squeezed orange juice. You are cooking dried figs and dates and sultanas. You can indeed have pulverized almonds if you like. I'm not a hazelnut person in this case. It will fill your kitchen. You slowly simmer it. You poke at it every so often.

Because we are Jews, of course, particularly the Italian tradition—the Turks and the Egyptians and the Syrians all argue about whether you should have more dates. Dried apricots is another possibility. They all argue with the Italians, and the Italians argue among themselves, of course. There's a Livorno charoset recipe and there's a Sicilian. I never worry about that.

But I will put in line the cooked version. I can hear both men and women—because I'm sure there ought to be a lot of male Jewish cooks here—saying, "I don't need to be cooking charoset." Yes, you do. It will change your life and make you a happier person.

JOANNE MYERS: You've even given us food for thought! With that, I really would like to open it to the floor.

QuestionsQUESTION: Don Simmons.

Very, very enjoyable. If there is not to be a two-state solution in the Middle East, would you foresee Israel retaining its Jewish character or its democratic character? Or is there a third way?

SIMON SCHAMA: This is the most important question, of course. The reason why Ariel Sharon came to the conclusion before he had his stroke—a lot of my friends in Israel think that, actually, if he had not had a stroke—and there are aspects of Ariel Sharon's career which I did not admire—the march on the Temple Mount, which triggered (it didn't cause) the Second Intifada, was a true catastrophe, and unnecessary.

But why did Ariel Sharon come to the conclusion, not just to abandon settlements in the Gaza Strip, but that there should be a two-state solution and there should be an exchange of territory for peace? The answer was—Menachem Begin came to precisely the same—we're not talking about kind of wet lefties here; we're talking about people from the hardcore of the right-wing Jabotinsky tradition in Israeli politics—was that it would simply be impossible, that Israel was founded to be, not just a Jewish state, but a Jewish democratic state, a democratic state, a light unto the nations, the only authentic, for many years, democracy in the Middle East.

And if it was going to do that, it couldn't actually annex Judea and Samaria, the West Bank, because either it would then be ruling over a disenfranchised—a huge number of Palestinians—and would be in the imperial position, which Zionism always, rightly, said it would not be, or it would abandon its—this is an argument, frighteningly, kind of going on, and not completely pessimistic. There are groups on the very hard religious, nationalist right who say, "Actually, we don't care that much about the democratic issue. We care about the Jewishness of"—but it seems to me an utterly profound, tragic contradiction in terms to say we can both be a clearly Jewish state and—what does that mean? A Jewish state ruling an annexed, huge Palestinian population.

That's not what Weizmann wanted. It's not what Ben-Gurion wanted.

I think there has to be—and this is hardly an original position; this is a position, actually, of Netanyahu, and it was certainly the position of Yitzhak Rabin as well and the position of Olmert and Tzipi Livni and the Sharm el-Sheikh negotiations, which very, very nearly happened. The Sharm el-Sheikh negotiations broke down over one, admittedly huge issue, and that was Ariel. Ariel is an enormous place. It's a city. Unlike Ma'ale Adumin, it's deep in the West Bank. The issue was sovereignty of Ariel and the sovereignty of the corridor to it.

Don't ask me how that's going to be solved. Ariel is conceived of as—if other settlements on the West Bank are going to be removed, then Ariel is going to be the place where the settlers were going to be offered a place to go to. This remains a specifically huge problem.

But all of those people did absolutely, as does Mahmoud Abbas—notwithstanding what has happened right now—for me anyway, it's either got to be a two-state solution or there is no solution; there is just an endless military fortress state. And time is not on Israel's side, for all sorts of upsetting reasons.

QUESTION: Susan Gitelson.

This was so fascinating. Let's take one of the points you make, when you show Moses Mendelssohn in Germany through emancipation and enlightenment remaining a Jew and yet contributing enormously to German and Western culture, but his grandson, Felix Mendelssohn, of course, has converted and brings so much to music. Then you have Meyerbeer, who is damned later by Wagner.

SIMON SCHAMA: Mendelssohn actually is named as the problem by Wagner, because he's dead. Wagner was a coward, apart from everything else. He was actually frightened of attacking Meyerbeer by name, because Meyerbeer was still alive in 1850, and very much a power in the land.

QUESTIONER: And had been his inspiration.

SIMON SCHAMA: Had been his patron.

QUESTIONER: So here we have a problem. We have people welcomed into society, emancipated. Yet they are not fully accepted. Many convert and are assimilated.

Just to bring it up to the present, we have paradise here, where everyone sitting here comes from whatever tradition and whatever religion and respects each other and is interested in learning about the others.

How can we promulgate this on a larger basis? And are there any other examples of minority groups that have been able to move into this kind of paradise?

SIMON SCHAMA: I am slightly confused by the question. The first one is, does the Moses Mendelssohn experiment always inevitably end in assimilation?

QUESTIONER: Right.

SIMON SCHAMA: As you very kindly and rightly said, the Meyerbeer story was intended in Volume 2 and in the program to show it doesn't always happen. Then there are people who do convert and who instantly regret it—Heine, of course, is the absolutely massive example there—and remain, really, even though technically Christians—they clearly don't like being one—remain deeply and profoundly in everything they write addressing themselves to the place of Jewish culture in Germany. Then there are others, like Schoenberg, who convert and, unlike Mahler, think better of it and have this extraordinary epiphany where they return to Judaism.

So there's not one kind of formula. A really dear friend of mine, when I told her about how I wanted to do a real Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) German program, which did not say that the fate ultimately was assimilation and/or the gas chamber—I said, "Here is the possibility of what Haskalah promised," and she said, "Oh, that old con." I said, "Well, it wasn't a con in Britain for us, and it wasn't a con in the United States."

The answer to can you can find a place where you can sustain a sense of being an American and a Jew—for yourself, it's Limmud. It's the possibility of doing the programs I have just done. It is, above all, actually delivering to generations to come after us an actually vital engagement.

I know the demographics of intermarriage and the loss of Jews are sobering. But you do what you can. You provide, not just a sense of the obligation of authority in stories about Jews, but a sense of, really, excitement and constant refreshment of what the Jewish tradition is, some things like—I'm not patting myself on the back, because I really didn't start this great kind of revolution which re-created Jewish art history. Actually, Cecil Roth did it. He was the first person to write a book on Jewish art history. But the whole sense of what a Jewish visual culture is, embedded in the Jewish museum in New York, in everything we know, really, about the way images have worked along with words—that's another example of something which can be made extraordinarily exciting and gripping.

Your second question was whether or not there are other cultures that have—as I said at the beginning, of course, there are. Cultures that are uprooted or that have an engagement with a different tradition do produce an astounding disproportionate flowering. The number of Asian-Americans who play European classical music better than anybody else is just a ridiculously trivial case in point.

There are many other—the Jews didn't invent this, but what happened to Jews, as I go into detail in the book, is that, inadvertently or not, what we did was to take the portable word with us. That's to say, when ethical norms and laws, Hammurabi and so on—we were not unique in being lawgivers in that way in the Middle East, as a kind of Semitic people. But we were unique in actually developing a simplified 22-letter form in which both ethical norms and a narrative of how we came to receive them could be transported with us, when all the usual markers of a people's existence—physical territory, land, palaces, fortresses, armies—were completely pulverized and destroyed.

The very first moment when the word "Israel" occurs in any historical document whatsoever is in the triumphal stone inscription, the stele, of the pharaoh Merneptah, who I think was Ramsses II's successor, in the 13th century BC. Israel appears in a list of those on whom the pharaoh's heel has trodden, along with various kinds of Arameans. It says, "Israel's seed is scattered. He is no more."

Actually, no, sunshine, that turns out not to be the case, because we move with our words. So there's that extraordinary tradition that has been made possible.

JOANNE MYERS: Unfortunately, our time has come to an end. I have to thank you for being always so refreshing and inviting us to be part of your story.