Shashikant Raut, 24, is a tribal farmer living in Pochade village, in Vikramgad block of Thane district, Maharashtra. Since adopting jasmine floriculture as a means to augment his income, he has been better able to support his family of eight, which is comprised of aged parents, a wife, two children, and two younger brothers.

His annual income is about $4,000 from the sale of organically cultivated jasmine flowers, seasonal marigold blossoms, and jasmine grafts. This income has helped Shashikant send his children to good schools, buy a motorcycle to help transport the delicate buds from his farm to the collection point in the village, and manage the age-related health problems of his parents.

He cultivates the jasmine on a plot measuring 279 square meters which he started with 130 saplings in October 2005. Subsequently he added another 1,100 saplings after about six months, and later on even more. Five months after the initial planting he was able to harvest an average of two kilograms of flowers per day, which sell for about $2.50 per kilogram on average.

Like Shashikant, many tribal farmers in the Vikramgad block of Thane district have benefited from a floriculture initiative that was started by the Maharashtra Institute of Technology Transfer for Rural Areas in 2005. The word mittra means "friend" in Marathi and "sun" in Sanskrit, symbolizing the rays of light that bring new life to the world each day. MITTRA was established as a nonprofit organization in 1993 with the mission of creating opportunities for gainful self-employment for rural families, especially disadvantaged groups, ensuring sustainable livelihood, enriched environment, improved quality of life and human values. This is achieved through development research, effective use of local resources, extension of appropriate technologies, and upgrading of skills and capabilities with community participation.

The Context: Maharashtra a Paradox of Prosperity and Poverty

Maharashtra has the image of being a developed agro-industrial state. Its growing population of 112 million people accounts for about 9.3 percent of India, while the gross state domestic product (GSDP) equates to about 14.7 percent of national GDP.

Yet Maharashtra has some of the poorest and most underdeveloped regions in the country. There are huge variations in per capita income prevailing among the various districts of the state. If the urban districts of Mumbai, Pune, and Thane are excluded, the average per capita income in Maharasthra drops to $1,010 from $1,329. The national figure is $835, and the per capita income in Gadchiroli, one of the poorest districts in Maharashtra, is only $128.

Gadchiroli has a large tribal population and is considered to be a "backward area" although it is rich in natural resources, flora, and fauna. This area has seen a lot of violence in the last three decades of Naxal (terrorist) activity. Poverty and limited livelihood opportunities have created a tenuous situation.

Small and marginal land holdings in the villages of Vikramgad block are far removed from the hustle and bustle of the Mumbai region, although they fall under the Thane district. Practically all the families living there were below the poverty line and dependent upon agriculture. Since the area is designated as a tribal area, the land technically cannot be sold to non-tribals in the open market and hence has not attracted commercial land developers. Fragmented land holdings, poor literacy levels, malnutrition, and temporary migration are prevalent along with the rain-fed agriculture economy.

Vikramgad is 110 kilometers from Thane city center (two hours by car, three hours by bus) and 166 kilometers from Mumbai. The region enjoys a tropical wet-dry monsoon climate, with a rainy season spanning the four-month period from mid-June to mid-October and a dry season lasting eight months. The mean annual precipitation in Vikramgad is 2.6 meters.

The predominant tribal groups in the area are Kokna, Warli, Thakar, and Katkari. The Katkari are categorized as primitive tribes by the government of India—victims of abject poverty, malnutrition, and exploitation, with high infant mortality rates.

In 1975, India recognized these people as the original inhabitants of the Western Ghats, bringing them under the purview of tribal law. In these communities a group of four to five hamlets constitutes a village, and affairs are regulated by traditional councils known as panchas comprised of five or more tribesmen (women are excluded).

The Sustainability Strategy: The Wadi Model Combined with Floriculture

A wadi is a small orchard covering one acre with crops like cashew, mango, amla, or any suitable fruit crop, with forestry species on the periphery surrounded by a productive live hedge. A typical orchard promoted under this scheme involves 40–60 fruiting plants and 300–400 forestry species along the border.

Organic floriculture was introduced as an intercrop in the wadi model in 2005 to ensure a perennial source of livelihood. It was essential to overcome the long gestation associated with horticultural activities and thus prevent the seasonal migration of the tribals, which would have led to neglect of the wadi.

The reasons for choosing floriculture were as follows: 1. Limited seed capital required (when activity is on a small scale); 2. Faster income generation compared to tree-based farming; 3. Ease of management, especially in cases of small farms; 4. Perennial income opportunities from flower sales; and 5. Potential for value addition. The start-up cost per farmer at the program's inception was about $20. MITTRA provided the planting materials while the rest of the costs were borne by participating tribal farmers.

Technical assistance was provided by MITTRA through on-site training sessions and the formation of farmer clusters (referred to as tukadis in Marathi, the local language). The farmers were made aware of techniques for optimum production through visits to commercial floriculture operations, discussions with other farmers, and advice from the MITTRA technical team. Monitoring was done on a regular basis to ensure that the interest and motivation of the participating farmers was maintained.

MITTRA made sure that the farmers had access to some source of irrigation (either channel, drip, or head load) before advocating perennial floriculture such as jasmine. A farmers' federation (Vrindavan Pushpa Utpadak Sangh) was set up to foster team spirit, develop leadership qualities at the grassroots level, and to build a strong village-level people's organization. There is no membership fee associated with the federation. The only criterion is that the member be a tribal farmer with an interest in jasmine cultivation.

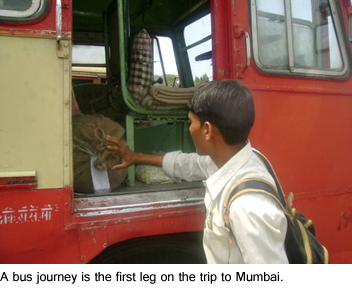

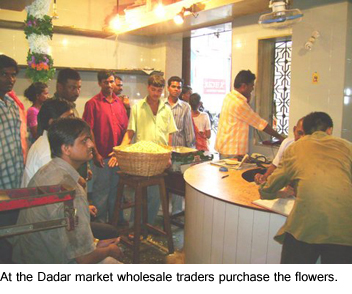

Accordingly a model of cultivating about 200 plants of organic jasmine (jasminium sambac, also known as mogra) on 500 square meters was developed. The flowers are sold in the Dadar market of Mumbai. This seemingly simple task is actually quite daunting when one considers that the delicate buds must traverse the distance under difficult conditions including overcrowded commuter trains and soaring temperatures (which can reach as high as 42 degrees Celsius). Buds are harvested at dawn and the farmers bring them to a central collection point in the nearby village. A representative of the farmers' federation transports the aggregated produce by road to the Thane station and from there to the Dadar market where it is sold to wholesalers at the prevailing rate of the day.

Impact Analysis

Ten farmers signed up for this program when it was launched in 2005. Over the years the program has seen a good response and, according to 2010 data, 430 farmers are now involved in floriculture as an income-generation activity. The money earned from the sale of jasmine flowers over the years has improved the education, health, and quality of life for the farmers. It has also helped to build their asset base through home construction and the purchase of vehicles and agricultural implements to aid floriculture activity.

The success of this initiative has been replicated at sites across Maharashtra and has helped to improve the lives of more than 3,000 tribal families. Over the years, other flower varieties like marigold, gladioli, rose, and tuberose have been introduced. Challenges including the highly perishable nature of the produce, poor connectivity from the hamlets to the Mumbai market, the vagaries of nature, and management of the interpersonal dynamics of the members make the entire task highly complex.

There is great potential for growing the range and scale of the business by tapping overseas markets, particularly the Middle Eastern and European countries, where these organic blooms can be used fresh or in processed form. They are far superior to chemically grown flowers in terms of their fragrance, physical attributes, and durability. The result would be a win-win situation for the farmers and the business houses, but taking it to the next level will require greater impetus and coordination with industry and government.

AUTHOR'S NOTE:

I wish to acknowledge my gratitude to Kailas Andhale, associate thematic program executive at BAIF Development Research Foundation in Pune, for sharing his insights and data which helped to build this piece. Sincere thanks go also to Shri Girish Sohani, BAIF president and managing trustee, for supporting and encouraging a journey that began nearly three years ago when I first started "wanting to find out" more about sustainable development—as a philosophy in action rather than an ad hoc activity, as it is often practiced by corporates to fulfill statutory accounting and reporting norms.

By researching various BAIF programs, it was indeed encouraging to see the impact in the lives of real people at the "base of the pyramid." Over the years, Mr. Sohani patiently answered my questions and queries, read several very rough article drafts, and gave me some strong and useful feedback. I am deeply indebted to him and his team at BAIF for all their support and cooperation without which this idea would have just remained a thought.