The Adivasi population of India constitutes about 8.14 percent of the total population—approximately 85 million people according to the 2001 census. These households traditionally derive sustenance through forestry, hunting, and primitive agriculture practices.

Yet seasonal migration to nearby cities has become a virtual necessity due to fast-depleting forest and natural resources, land erosion, and lack of access to basic health and hygiene. Once in the cities, these landless workers live in deplorable conditions and often get exploited by middlemen. They are also not able to claim state government benefits due to a lack of identity. Ineffective labor laws make their situation very difficult, especially for women.

Large sections (some 36 percent) of the tribals subsist in a state of deprivation. Adivasis typically practice rain-fed agriculture, and the small and marginal nature of their land holdings complicates food security.

Published literature [PDF] in this area has emphasized the need to connect small and marginal farmers to remunerative markets to help them realize better returns. A lack of capital and purchasing power affects the conditions and the scale of operations, while a lack of market linkages hampers the seed-to-market journey. Very often the input costs are far greater than the output.

What Is the Wadi Model?

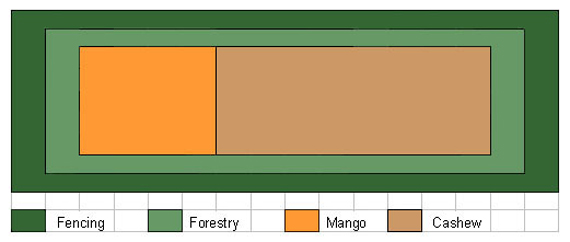

Some relief has been found using the wadi model. The word "wadi" in the Gujarati language means a small orchard, generally covering one acre with crops like cashew, mango, or any suitable fruit, with forestry species on the periphery and a border consisting of a productive live hedge. A typical orchard promoted under this scheme involves planting 40–60 fruit plants and 300–400 forestry species along the border.

The Rationale

The idea came from Manibhai Desai, founder of Bharatiya Agro Industries Foundation (BAIF) and a follower of Mahatma Gandhi. Desai believed deeply in the Gandhian philosophy of revitalizing the village economy in order to fortify India's agrarian economy. He felt that it was important to rehabilitate the tribals in their own environs and provide them with a livelihood solution.

The Vansda (Gujarat) region was representative of the typical problems affecting most tribal communities in that there was indiscriminate destruction of forests, as well as scarcity of food and drinking water. The tribals were practicing rain-fed agriculture and hence cultivation was only possible during kharif. Production was poor due to a lack of improved cultivation practices.

After the kharif harvest, families had no option but to migrate to adjacent cities (Vapi, Valsad, and Nasik) in search of livelihood. Migration was characterized by exploitation and the discontinuation of children's education. Lack of health care options, weak communication, and poor housing and sanitation added to the problems.

Hence after evaluation of various alternatives it was decided to cultivate mangoes and cashew crops. Some of the factors that made these two crops the preferred choice were the agro-climatic suitability, robust demand, good shelf life, and the possibilities available for processing mangoes into various by-products such as pulp, pickles, juices, jam, canned fruit, and baby food, as well as good local and international markets for cashews.

However the endeavor required a lot of hard work, team work, and patience since the trees started bearing fruit only after nearly 4–5 years. BAIF played the role of facilitator, trainer, and guide in helping the community to accept the long and challenging task of preparing the groundwork required to succeed. Regular interaction with the participating members was necessary to encourage the 42 tribal families that participated in the program when it was first launched in 1982.

The journey was arduous and the extreme climate made tending to the saplings a challenging experience. In areas where irrigation options were not available, participating tribal members would carry water in pots atop their heads for hours to water and tend the saplings. This had to be done daily for nearly 3–4 years before the fruit plants stabilized!

The participating tribal families earned in the range of about $160–200 from the intercrops—cereals, rice, pulses, and some vegetables such as brinjals (eggplants) and tomatoes—per year from the first year. The major income of approximately $600–800 per year came after 6–7 years when the orchards started bearing fruit regularly.

Linking the Tribal Farmer Cooperatives with Industry

In a symbiotic arrangement under the aegis of the wadi program, a relationship with the Indian fast-moving consumer goods major ITC was initiated in 2007–2008. The main deterrent in organic farming is the steep cost of obtaining organic certification, which is out of reach for small and marginal farmers. ITC bore the cost of obtaining the organic certification for mangoes and in turn was assured of quality mangoes to be used in its products. In 2010, some 1,150 MT of mangoes were sold to ITC. In a typical year, participating farmers were able to see a 33 percent increase in their net selling price as compared to the traditional supply chain.

This turned out to be a win-win situation for both parties. ITC got the organic mangoes that were used in its baby food products, while the tribals got an assured client and a higher value for their produce.

Conclusion

The success of the wadi program was possible due to the dedication and perseverance of the key stakeholders: the tribals, BAIF, and the funding agencies. This seed-to-market initiative helped to solve the basic needs of the tribals: food security, job options, healthcare, and education.

The success of the program has been further replicated in other Indian states such as Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh. The key success factor that made this program so effective was the symbiotic effort of BAIF and the tribals. BAIF brought to the partnership the knowledge, access to R&D, and experts who helped to navigate the initial turbulent times. The villagers, on the other hand, invested in the project through their efforts and by allowing the aggregation of their most precious resource—their land. It was their faith and perseverance that made the project a resounding success.

The fruits of their labor became a beacon of hope to other tribal families, leading to an expansion of benefits and the scope of the program as it evolved over the years.