This article is in response to the Carnegie Council Global Ethics Forum TV show A Conversation with Bill McKibben and was first posted on the Fordham University Center for Ethics Education website on December 14, 2016.

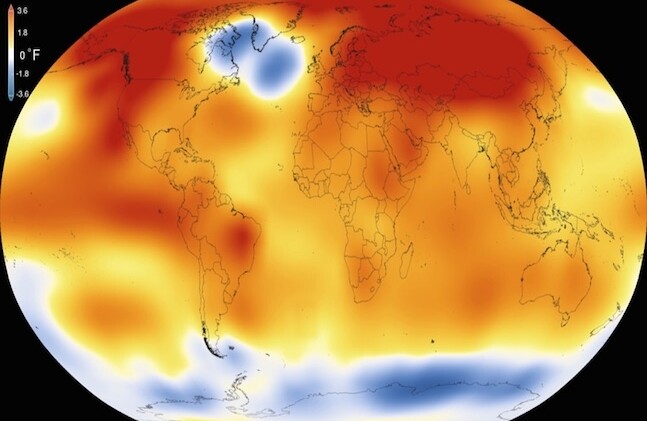

Often when a problem is too big or too scary we throw up our hands and announce that "There is nothing we can do" to solve it. Admittedly, climate change feels like one of those problems. It seems like a quagmire of depressing facts and statistics. It is now scientific fact that the polar ice caps are melting, our oceans are rising and becoming more acidic, and if we do not curb our consumption of fossil fuels, our planet will be rendered unlivable. The plethora of disturbing information on climate change is enough to cause anyone to have a sleepless night or make them wish they had never heard the truth about our warming planet. However, ostriches with their heads buried in the sand do not get much done, and once you know some truth, you cannot un-know it. And so the question at hand is not "Is climate change happening?" for that question has been answered in the affirmative (although climate change deniers would like to see this issue removed from our national political discourse). The question right now is "What are we going to do about it, if anything?"

Bill McKibben, environmental scientist and founder of 350.org, has spent his career writing about climate change and mobilizing communities as an activist for the cause. The mission of his website reads: "We believe in a safe climate and a better future— a just, prosperous, and equitable world built with the power of ordinary people." This statement is in no way frightening beyond the scope of comprehension. In fact, it is probably what most people want out of the future. Unfortunately, the direction we are headed in is not conducive to this safe and equal future. In fact, it is quite the opposite. If we continue with our current rate of fossil fuel burning, we could be left with a planet that is ungovernable, uninhabitable and unrecognizable. This is a terrifying thought, but should climate change activists refrain from telling the truth about our planet’s situation?

At one point during the Carnegie Council's featured video "Global Ethics Forum: Ethics Matter: A Conversation with Bill McKibben," McKibben was asked about instilling fear in the general public so much so that the sheer magnitude of the problem may compel them not to act. To this, McKibben replied, "reality is what it is, and we should describe it." In fact, it could be said that experts on ecology, such as environmentalists like McKibben and climate change scientists, have a duty to make this knowledge available to the public.

Presently, we have seen enough "100-year" storms and floods to be convinced of the boundless power and undeniable truth of climate change. Activists and scientists cannot be charged with attempting to use unwarranted scare tactics. However, if they have been guilty of scaring the public into action in the past, is that such a bad thing?

From a utilitarian perspective of ethics, the ends justify the means and thus, whatever actions are taken are ethical as long as they promote the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Hence, even if information was disseminated in a frightening way, if it caused a positive change in society, it was ultimately a good. Similarly, from a deontological view of ethics, individuals have a duty to promote moral ends for the common good. From this perspective, ecological whistleblowers, because their intentions are good, are moral beings trying to enact positive changes in society.

Certain professions, such as teachers and social workers, are mandated reporters. This means that when they see a violation of human rights, such as a child who is clearly malnourished or abused, they must contact the authorities. If they fail to contact the authorities, they can be held responsible for the well-being of the child and their job and licensure can be put in jeopardy. In a way, scientists and activists are mandated reporters whose concern is not for the good of one individual or child, but for the good of all humanity and our entire planet. However, now that we know unequivocally what is happening to our planet in terms of its changing climate, and what that will mean for humanity in the decades to come, the question is now posed to us: What will we do about it, if anything?

The oil and gas industry is "the most powerful industry on Earth," says McKibben. Indeed, this industry not only decides what energy we use, but how it will be extracted and transported, what countries it is sold to, and how expensive it will be. Oil and gas companies have huge sway in Congress and our government at large. President Obama has said that we have enough energy to last us one hundred years, yet the industry spends "$100,000,000 a day looking for more sources of fuel." Thus, McKibben calls them a "rogue industry" because they are now defying the laws of chemistry and physics, and are consciously altering the chemical makeup of our planet. Moreover, when this industry makes a mistake, the world suffers. On April 20th, 2010, a seal on a B.P. operated oil well in the Gulf of Mexico failed, and commenced "the worst environmental disaster in U.S. history," as well as the worst marine environmental disaster in human history. "For 87 straight days, oil and methane spewed" into the Gulf. By the end of the ordeal, "an estimated 4.2 million barrels of oil" were released into the Gulf waters. This disaster had serious and long-lasting consequences for the tourism and fishing industry of the Gulf. One would think that after such disasters the human race would come together in a concerted effort to stop such atrocities against humans and nature, but apparently we do not learn from our mistakes.

The time has come to act on climate because we can no longer afford not to. We know what consequences are in store for us if we continue on our current trajectory. Although there are many movements aimed at stopping individual projects, such as the opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline, we now need a comprehensive plan that curbs, and eventually stops, carbon emissions. Bill McKibben suggests imposing a carbon tax on the energy industry. This is probably the only way that will subdue the energy industry's power.

Not everyone is cut out for activism and certainly only a small portion of the population has the desire and ability to become a scientist. However, if we are to leave a habitable planet to our successors, if we are to protect the non-human species living on our planet (some of which have lifesaving potential for humans), and if we are to sleep soundly at night knowing that we did everything that we could, then we must act now. The human race now has an opportunity to come together to protect our planet, and really, what do we have to lose? Best case scenario: we save our world. Worst case scenario: we foster a culture of fraternity and brotherhood—the scope of which humanity has never seen before.